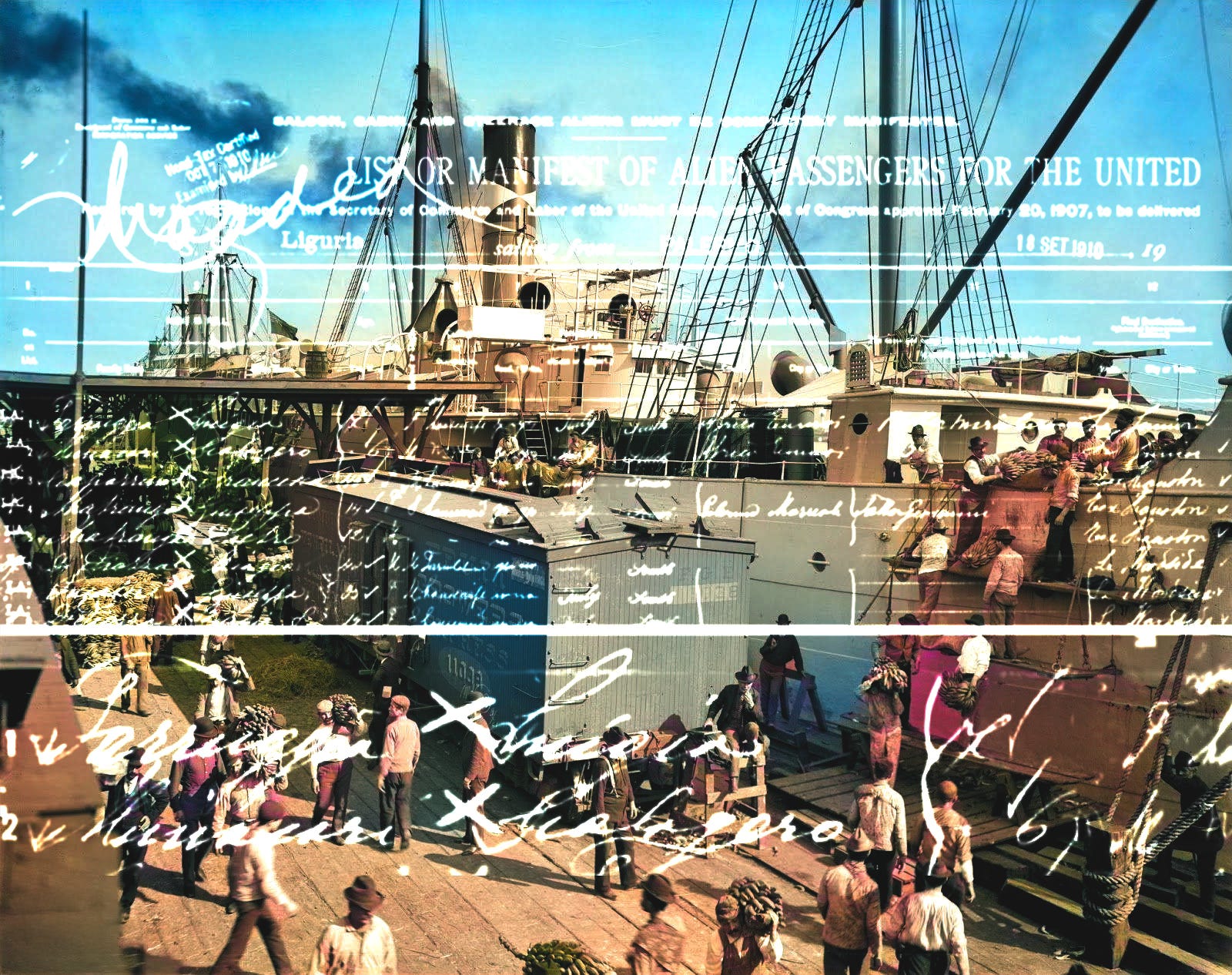

Oct. 8, 1910: The Liguria

Carlos Marcello's story begins with a teen mother and her baby leaving Sicily, alone in the belly of a packed steamship, to join her husband in New Orleans.

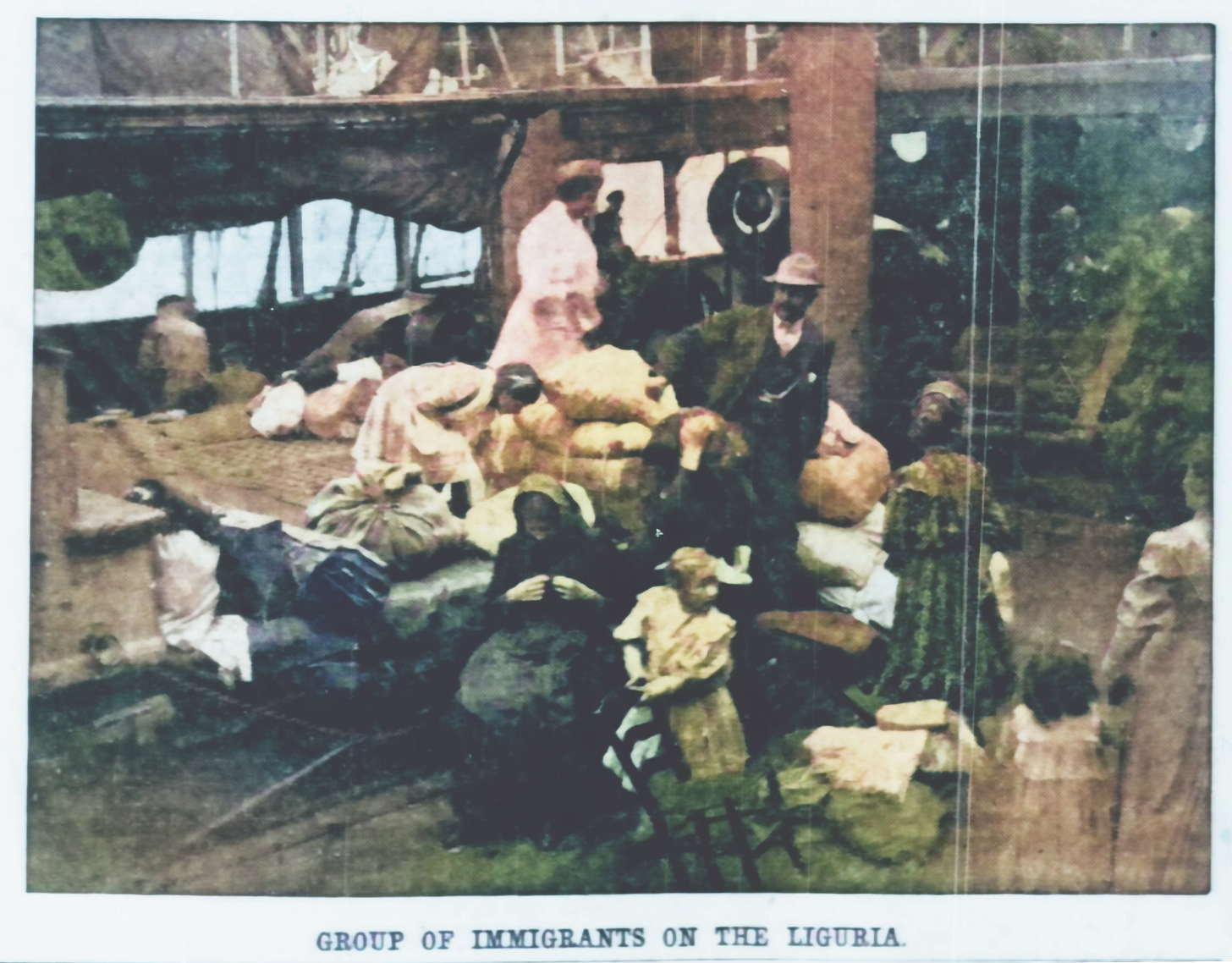

The night before 17-year-old Luigia carried her infant son off of the steamship Liguria and into the embrace of a mad, accidental, improbable, and enchanting city; the night before her husband, 27-year-old Giuseppe, met his first child for the first time; before they began building a new life in a new world; before Luigia became Louise and Giuseppe became Joe and before Minacori became Marcello, the ship’s captain, Salvatore Anfosso, invited her and all of the other mothers of small children from steerage up to the recently-vacated cabins in first class. It was an unusually grand gesture, giving the cabins away for free that night, even for Captain Anfosso, who was somewhat of a minor celebrity in New Orleans thanks to the years he spent shepherding Sicilian immigrants and seasonal workers, the so-called “birds of passage,” between the lemon groves of their ancestral home and the sugarcane fields of their adopted one.

Under Anfosso’s command, the Liguria was a 5,000-ton money-making machine, a fast and reliable transatlantic workhorse capable of shuttling as many as 2,000 passengers from Palermo to New Orleans in only three weeks, and she was even quicker on the way back. “The Liguria has been specially built for service between Mediterranean ports and the United States, and it is provided with steam heaters for winter and a system of electric fans,” the Daily Picayune reported in August 1904 in a story announcing the newest addition to the local Italian fleet. “It has large, smoking rooms, a well-filled library, and magnificent drawing rooms. There are two dining rooms on the promenade deck, with two rows of large windows, ensuring ample light and ventilation. In the construction of interior accommodations, careful attention has been given to the arrangement of cabins, to secure every comfort to the travelers.”

Luigia was already familiar with the Liguria. For their honeymoon, Giuseppe wanted to take his bride on a tour of New Orleans, so he paid the $76 fare (approximately $2500 in today's dollars) for a pair of tickets departing Palermo aboard the Liguria. It was to be Luigia’s first time in America, but for reasons likely lost forever to the passage of time, she never disembarked from the ship in New Orleans. Both of their names were listed and then crossed out of the ship’s passenger manifest, though only Luigia’s entry contained the notation “no entry,” suggesting that while her husband, who had already taken three previous trips to America, was admitted, she stayed on board and headed back home.

Luigia and Giuseppe had tied the knot on February 8, 1908, two days after her 15th birthday, exchanging their vows inside the sanctuary of the Sainte-Croix Church in Tunisia, the first and only Catholic chapel located within the Medina of Tunis.

Their families, the Minacoris and the Farruggias, shared a bond and a history stretching back generations and across multiple continents. Both were rooted in Ravanusa, a tiny, cliffside village on the foothills of Mount Saraceno in southern Sicily, and both found work on the other side of the Mediterranean in North Africa in Tunisia. Like many Sicilian couples, the union of Giuseppe and Luigia began with a proposal negotiated and drafted by their parents. It wasn’t an arrangement either of them was forced to accept, but a match they were encouraged to cultivate.

The Minacoris left Sicily when Giuseppe was seven; the Farruggias arrived when Luigia was just seven months old. They settled only a few blocks from one another on the outskirts of Tunis, the besieged capital city of a fallen royal kingdom. Despite their time away, Sicily would continue to claim both families as its own. A year after Luigia and Giuseppe married, word finally reached Ravanusa, and a fastidious town clerk recorded the union, affixing a note on the margin of Giuseppe’s birth certificate.

At the turn of the 20th century, Tunisia, a battlefield and graveyard of ancient civilizations and powerful empires since the beginning of recorded history, was a protectorate of France, which took the country by force in 1881 after 300 years of Ottoman rule. Although Tunisia became part of France’s vast colonial empire, the French were not interested in becoming part of Tunisia, a predominantly Arab country. France’s presence in North Africa had less to do with cultural or historical ties or trade advantages than it did with containing Italy. In French Tunisia, Sicilians comprised nearly 10% of the entire population, representing the largest non-Arab community in North Africa, well over 100,000 people.

Giuseppe Minacori was one of those birds of passage, part of the flock that migrated to Louisiana for the autumnal sugarcane harvest, or la zuccherata, as it was known in Italian. He first arrived in America in 1903, aboard Captain Anfosso’s previous ship, the Manilla. His sister, Crocifissa, and her husband, Ciro, were already living in New Orleans on St. Joseph Street. He spent a few sleepless nights with them before Luigi dell’Orto, the New Orleans agent for the Italian Line, found him a job downriver in Plaquemines Parish. For three months, Giuseppe cut sugarcane at a place that still called itself a plantation even though the opulent mansion that had once dominated its grounds, left fallow and forgotten after the war, was now nothing but a pile of rubble.

The work was backbreaking, but Giuseppe, who stood 5’3” tall, was all muscle and might, granite and bronze and volcanic ash. He would push himself beyond the point of exhaustion, as evidenced by the missing middle finger on his left hand. It helped, though, that the sugarcane season wasn’t long, from October to January, and the pay, $1.50 a day, was as much as anything he could have made back home. He’d returned for the harvest in 1904 and again in 1906. And he would’ve gone in 1905, but that summer, one of United Fruit Company’s steamships carried yellow fever to the Thalia Street Wharf in New Orleans, along with a smuggled shipment of contraband bananas from Belize. A Sicilian dockworker was infected. Within a couple of months, a yellow fever epidemic swept across New Orleans, claiming nearly 500 lives and placing the entire city under mandatory quarantine.

Giuseppe always made sure there was a job lined up for him in Louisiana before making the long voyage to the other side of the Atlantic, knowing how in recent years, hundreds of Italians took the three-week journey to New Orleans only to be turned right back around, either because the seasonal positions were all filled or because the harvest was too paltry.

On his first trip in 1903, New Orleans had looked nothing like Giuseppe imagined of America, nothing like anywhere he’d ever seen. After disembarking, he pressed and shimmied through the orchestrated chaos of the Northeastern Fruit Wharf and finally spilled out onto the oyster-shelled streets of the lower French Quarter, an enclave called Little Palermo. In Little Palermo, he felt a rush of recognition.

Many of the names adorning the city’s storefronts were already familiar to him: Baratina, Catanzaro, Clesi, Manale, Radosta, Mancuso, Paretti, and Montelbano. Antonio Monteleone owned and operated a handsome 64-room hotel on the corner of Royal and Iberville. Angelo Brocato had moved to town and planned to open an ice cream parlor on Decatur Street. Further down Canal Street, outside of the Vieux Carré, as the French Quarter was more commonly known at the time, Sebastian Mandina built a grocery store and ran a popular restaurant. Before any of them came to town, Pietro Carmada’s son Emile cemented New Orleans’s reputation as one of the world’s top destinations for fine dining when he opened his restaurant on the corner of Washington and Coliseum in Uptown, which carried the surname his father adopted after immigrating from the tiny island of Ustica in 1852: Commander’s Palace.

He may not have known all of their stories, but all of these men, Giuseppe realized, were Sicilian.

Little Palermo served as a gateway for those traveling by steamship, a neighborhood that had risen in tandem with the development of the harbor along the Mississippi River and served as “a sort of home port, base camp, and central marketplace around which satellite communities of Italians (field laborers, fruit and vegetable farmers, seaman, dockworkers, market vendors) orbited for over half-a-century.” Primarily a collection of two and three-story brick structures that were originally the homes of affluent Spanish and French families, the neighborhood’s composition began changing in the 1840s as families moved out of the Quarter and property values plummeted. Gradually, its buildings were modified into tenement housing or subdivided into mixed-use rentals, with little concern for ventilation, sanitation, or overcrowding. To some locals, especially upper-class uptowners, the enclave of Sicilian immigrants was a crime-infested hotbed of disease, illness, and squalor, beyond any redemption other than demolition. But for people like Luigia and Giuseppe, Little Palermo was both a front door and a living room for their entire community or, as sociologists Anthony Margavio and Lambert Molyneaux put it, “(a place that) served to soften the transition from the old country to the new, insulating and sheltering Italian immigrants from a sometimes harsh and often indifferent world.”

At the turn of the 20th century, Little Palermo may have been the most difficult place to live in a town known as the Big Easy, but its proximity to the riverfront harbor wasn’t its only appeal. The neighborhood had also catalyzed around the French Market, a crown jewel of New Orleans and the pride of the Sicilian-Italian community. For Giuseppe, the French Market was always the highlight of his trips to New Orleans: Six blocks and 550 stalls of dry goods and fresh produce from all over the world. The French Market was sometimes called the Sicilian Market because, like the commercial docks and wharves lining the riverfront, Sicilians ran the whole show. More than 1,000 Sicilian vendors worked in the market’s grocery stalls and pushcarts, monopolizing the market’s leases. Indeed, by 1910, Sicilians effectively controlled and operated the city’s entire food supply chain.

Giuseppe wouldn’t work at a sugarcane plantation for long, he assured Luigia. He’d been inspired by New Orleans, and he dreamt of starting his own produce business, with fruit and vegetables grown in his own garden, next to his own house, which he’d sell all right there in the French Market. Luigia knew how ambitious and tenacious he was, and she believed him without any hesitation, even if she also understood the odds were stacked against them. Giuseppe’s dream was no different than the one shared by hundreds- if not thousands- of other Sicilian emigrants already in New Orleans.

From 1876 to 1914, a mass exodus of 14 million Italians fled their home country in one of the largest voluntary mass emigrations in world history. Of those, approximately 56% moved across the Atlantic, while the remaining 44% moved to another European country, with France, Switzerland, and Germany taking in exponentially more Italians than anywhere else. Many intended the move to be temporary, and while some eventually returned to Italy, most were gone for good. All told, four million people permanently relocated to the United States during the Italian diaspora, primarily to New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, major East Coast ports of entry in cities with burgeoning Italian immigrant communities.

New Orleans, Queen City of the South, was also a popular port of entry, and in 1910, it boasted the eighth-largest population of Italian immigrants in the nation. However, the Italian immigrant community of New Orleans was built differently from anywhere else. Unlike other U.S. destinations, where the vast majority of Italians came from continental Italy, with only about a quarter coming from Sicily, in New Orleans, Italian immigrants were almost exclusively Sicilian. According to congressional reports, “more than 99%” of the Italian emigrants who arrived in New Orleans in both 1891 and 1892 were Sicilian. A decade before, the split between continental Italians and Sicilian-Italians who came to New Orleans was roughly the same as other U.S. ports of entry. Today, the Crescent City remains “the only American city whose Italian population is almost exclusively of Sicilian origin.”

What happened? Why did Sicilians start moving to Louisiana? Why did people like Giuseppe Minacori and Luigia Farruggia leave?

To some extent, our ability to understand the phenomenon of Sicilian immigration in Louisiana is hampered both by the conflicting and ambiguous accounts of the number of Sicilians who came through but not to New Orleans and by the fact that Louisiana deliberately attracted temporary, seasonal workers, not permanent residents, from Sicily. Unfortunately, much of the early scholarship on Sicilian immigration in New Orleans failed to consider those factors, resulting in reporting that grossly inflated both the population of Sicilian-Italian immigrants permanently living in New Orleans and the total number of Sicilian-Italian seasonal workers who came through the Port of New Orleans.

“There is no way to tell accurately how many immigrants responded to the efforts to attract workers to the sugar plantations. Estimates range from a low of 16,000 to an improbable high of 80,000,” Anthony Margavio and Jerome Salomone explained in Bread and Respect: The Italians of Louisiana. “It was, however, the impetus of the sugar industry that opened the ‘immigration gates’ to Louisiana from Italy. Before those gates were largely closed by the Immigration Act of 1924, over 100,000 Italians had come through the Port of New Orleans as immigrants to the United States of America.”

Despite the contradictory and confusing methods used to measure the full scale of the so-called “Sicilian surge” in New Orleans, census reports and immigration records from the Port of New Orleans offer a rough approximation of the total population of Italian immigrants living in Louisiana when Luigia and her infant boy arrived on the Liguria. “The largest contingent of Italian, predominantly Sicilian, immigrants settled in Louisiana,” Jessica Barbata Jackson wrote in Dixie’s Italian. “In 1910, 43,000 Italians (foreign-born and native-born) resided in Louisiana; by 1930, nearly half of all foreign-born families in Louisiana were Italian.” According to the 1910 Census, 8,065 of the 19,634 (or 41%) foreign-born Italians were in Orleans Parish.

The most common explanation for Louisiana’s unique appeal to Sicilians, at least at the time, was that Sicilian immigrants, fleeing economic instability and political turmoil back home, were drawn to the Gulf South because its climate was similar to Sicily’s, and so were the jobs. If you could pick lemons, the argument went, you could raise cane. (Incidentally, Sicilians learned how to make sugar from the Portuguese, a century before Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville founded New Orleans). But it strains credulity to believe that Sicilians just spontaneously began showing up in Louisiana simply because of the culture or the climate.

In his book Geographies of New Orleans, Richard Campanella, a geographer extraordinaire at Tulane University’s School of Architecture, argued the attraction was mutual. “It was both a case of Sicilians selecting Louisiana and Louisianians selecting Sicilians, from the 1840s to the 1910s,” he wrote. Indeed, one of the main reasons Sicilians came to New Orleans was because the trading routes and commercial exchanges between Sicily and New Orleans had been established decades before the diaspora. “Shipping lines had been in place between Palermo and New Orleans since the early nineteenth century. Cotton and other Southern exports were shipped to the Mediterranean region, and citrus fruits and other dry-land agricultural products came in return, often accompanied by Sicilian merchants and some families,” Campanella wrote. “The American tropical fruit industry can be traced to New Orleans, which in turn can be traced to Sicilian and Italian merchants in the antebellum era.” In other words, Sicilians came to New Orleans because Sicilian ships were already coming to New Orleans.

Equally compelling was the fact that Louisiana actively and specifically sought out Sicilians. In 1866, in the aftermath of the Civil War, state lawmakers approved the creation of a new agency, the Bureau of Immigration, which was tasked with recruiting foreign workers. Before the war, the state’s agricultural productivity had depended on slave labor, but since that was no longer an option, planter elites and their allies in government began searching for the cheapest available alternatives.

Unlike other Southern states, Louisiana had two unique and sometimes competing plantation economies in two distinct geographical regions. The culture and conditions were different in the piney hills and prairies of northern Louisiana than in the salt marshes and swamplands of southern Louisiana, and so were the crops. For several reasons, including the transformation of the state’s cotton industry from a plantation-based model to a sharecropping and crop-lien model and the sugar industry’s comparatively early adoption of a wage labor system, the work was in sugar, not cotton. “A legacy of French and Spanish imperial ambitions engulfed by the Anglo-American world, and a bastion of Roman Catholicism encircled by evangelical Protestantism, southern Louisiana was—as it is to this day—a place unto itself,” wrote John Rodriguez in Reconstruction in the Cane Fields. “Its ante- and postbellum uniqueness, however, also owed to Queen Sugar’s reign in the land where cotton was king. Southern Louisiana was a slave society, but that was only half the truth: it was also a sugar society.”

Initially, the political vacuum left in the war’s wake and the dysfunction of Reconstruction stymied recruitment efforts, and the campaign for foreign labor remained idle until 1881, when the Louisiana Sugar Planters Association launched the Louisiana Immigration Association, an affiliated spin-off organization that served as a conduit between its member businesses, state and federal immigration agencies, foreign governments, the Louisiana Department of Agriculture, and the owners and agents of steamship lines. After initiatives to recruit foreign workers from China and Spain proved futile, the state narrowed its focus and worked in tandem with sugar planters to lure in Sicilians for the work.

In 1906, Charles Schuler, Louisiana State Commissioner of Agriculture and Immigration, explained how he believed the state could learn from its campaign for seasonal workers to attract “quality” foreign immigrants as well:

The only answer that I can give is to advertise. Advertise in every possible way. Furnish your immigration office with sufficient means, so that agents familiar with the resources and possibilities can come in personal contact with the prospective home seeker…. Distribute Louisiana’s literature, translated in the immigrants’ native language. Show the people of the old world in every possible way that Louisiana is an ideal state for a new settler. Show them the magnificent opportunities in agricultural pursuits, the thrifty and progressive towns and cities, the health and hospitality of Louisiana, the schools and religious advantages, [and] the splendid transportation facilities. Talk up Louisiana by telling the truth about her.

Giuseppe Minacori didn’t dream of working at a rundown sugarcane plantation in the sweltering heat of the Deep South for the rest of his life. He first came to Louisiana for the same reason nearly every other worker from Sicily came: Louisiana needed him, temporarily at least. No one asked him or Luigia to stay. They decided to return, permanently, largely because New Orleans already had a thriving, hard-working, and increasingly influential community of Sicilian immigrants, a community that had already reshaped the city’s built environment, its culture, and, perhaps most significantly, its cuisine, a community to which their membership was a birthright.

As eager as they were to start their new life, Giuseppe wanted to ensure he had a stable job and that they had a home before Luigia left her family in Tunisia, tasks that became even more urgent when Luigia told him the good news. He was about to become a father. So, for the second consecutive year, Giuseppe was back on the Liguria in September. This time, though, his ticket was one-way.

The momentary joy he felt after learning he’d soon be a father was quickly washed away by a combination of overwhelming guilt and regret. Since he couldn’t be there, he asked his older brother to check on her occasionally. Luigia lived with her mother Maria, and Giuseppe knew she would not be alone. He was the one alone. Nonetheless, it reassured him when his brother promised to make daily visits and to guarantee Luigia’s safe passage to America.

Giuseppe knew he could no longer make ends meet as a seasonal worker. He needed something full-time and year-round. So instead of writing the dell’Orto Agency, he contacted his brother-in-law, Ciro, and asked if he had any ideas or advice. Ciro and Crocifissa were no longer living on St. Joseph Street. They were now 30 miles northwest, on the shores of Lake Ponchartrain, outside of Frenier, Louisiana, a German settlement originally named Schlösser that had been built around its railroad station and was primarily known for its cabbage, sauerkraut, and ample supply of cypress timber. If he made it up to Frenier, Ciro had a job waiting for him. Giuseppe readily accepted. The sugar industry had been struggling after a series of unlucky breaks, and the money wasn’t what it used to be. As it turned out, he wasn’t the only passenger on the Liguria that season who decided to look elsewhere for work.

“For the first time since the inauguration of the immigration movement in Louisiana, a big ship has arrived here with more than 400 aliens and not a single one of them has been secured for the plantations and factories of the State through the Immigration Department,” The Daily Picayune reported, surmising that Italians, “unlike the Greeks and Austrians,” don’t “come across the ocean without knowing what they are going to do.”

The baby arrived on Luigia’s 17th birthday, February 6, 1910. (The day is significant among Sicilian Catholics. Three hundred and five years earlier, on February 6, 1605, a boy named Filippo Latini, who would later become a Capuchin friar and take the name Bernardo, was born in Corleone. When he was finally canonized in 2001 by Pope John Paul II, Bernard of Corleone became the patron saint of Mafia victims.) According to the court testimony of a U.S. immigration official in 1963, a birth certificate was filed with the French Tunisian government, a copy of which had been obtained by the Department of Justice, though both the original document and any copies of it were subsequently either lost or discarded. However, a copy of his certificate of baptism, corroborating both the date and the location of the child’s birth, was translated from French to Italian and recorded in the municipal register of Ravanusa, Sicily, in 1912. He was baptized in Carthage on March 28, 1910, at the parish of Saint Croce, alongside his godfather, Salvatore Broccolieri, and godmother, Grazia Insulla.

The Liguria left Palermo on Sunday, September 18, 1910, on a journey that stretched out of the Tyrrhenian Sea, past the Straits of Gibraltar, across the Atlantic Ocean, through the Gulf of Mexico, and up the mouth of the Mississippi River. She carried 625 souls, including Luigia and her baby boy, and 571 other Italian emigrants. The Daily Picayune found it “interesting” that there were so many passengers since “it has been several months since a number arrived at this port.” Actually, it’d been well over a year, and the city wasn’t exactly prepared to roll out the welcome mat.

Late that summer, there were reports of a cholera outbreak in parts of Italy, news that slowly trickled across the Atlantic and sent New Orleans officials into a panic. For years, they’d been lobbying the federal government for a new customs and immigration facility, and they worried the city could not efficiently process so many new arrivals all at once, especially if they had to be quarantined. Their fears were not unfounded.

When the Liguria made her maiden voyage in 1904, she carried a record-setting 1,391 Italian emigrants. Newly enacted laws required immigration inspectors to perform more rigorous screenings of foreign nationals, and because the Port of New Orleans didn’t have its own intake center, screenings for all 1,391 passengers had to be conducted on board. It was a nightmare.

“Captain Stretton, in charge of the Immigration Bureau at New Orleans, and his assistants worked nearly fourteen hours a day for five days before they could conclude the examination, which was held on board the Liguria, in the middle of the river, and under peculiar hardship for them and for the immigrants. No other way out of the difficulty could be had because, as long as the examination is going on, it is necessary to exercise the utmost caution lest some of the immigrants escape,” The Daily Picayune explained. “New Orleans has no place to receive the immigrants as they arrive, so that they may be permitted to leave the ship and be safely and comfortably housed on shore, pending their release after having passed the immigration officers’ inspection. So the examinations on board were held under the most uncomfortable conditions of crowd, noise, and hampered space.”

After five days, authorities denied entry to nearly 100 passengers on that maiden voyage and ordered them to return to Italy. Appeals were filed with the Department of the Treasury on behalf of some of the emigrants who were turned away, which meant the Liguria had to stay put in New Orleans while those passengers, now considered legally detained, awaited a decision. Late one night, two of the detainees “clambered over the ship’s side, jumped to the wharf, and fled ashore.” Both men escaped and were nowhere to be found. Federal agents, exasperated, arrested the ship’s commander for violating immigration laws by “permitting the landing of these two alien citizens of Italy without the permission [of the United States].” The Italian Line threatened to pull up anchor and never return to New Orleans, and the Italian government threatened to turn off its spigot of seasonal workers by tightening travel restrictions.

Eventually, the Americans blinked. Federal officials made assurances about prioritizing the construction of a permanent, stand-alone immigration facility, and in the meantime, New Orleans port commissioners agreed to install temporary metal sheds. An international diplomatic disaster was avoided. A few months later, when the Italian Line delivered 676 Italian emigrants to New Orleans on the steamship Vincenzo Florio, the ship’s captain, Giovanni Orango, had been so impressed by the “great improvement” at the port and the “splendid work” of the immigration service he promised that if conditions continued to improve, he’d urge the Italian Line to begin offering monthly service to New Orleans, instead of once every three months. “Captain Orango believes there is not enough encouragement to immigrants in this port. In his opinion, a landing station should be established…. The officials in charge have done, and are doing, their best, but the physical facilities for taking care of the immigrants are woefully deficient.”

Nearly six years later, there were few signs of improvement. The Italian Line’s shuttle from Palermo to New Orleans was still running on a quarterly schedule, never again carrying more than 1,000 passengers at a time, and immigration screenings and customs inspections were still being conducted in temporary metal sheds. The system worked as long as the line kept moving, but if a large number of passengers had to be detained or quarantined, a solution would need to be improvised, quickly. Otherwise, there was a real risk of threatening public health or creating a humanitarian disaster.

“Passengers will be detained until representatives of the United States Marine Hospital and Quarantine Service can determine whether any of the Italians came from the cholera-infected districts or if there is any source of infection,” the New Orleans Item assured its readers in September of 1910, two weeks in advance of the Liguria’s scheduled arrival in New Orleans, neglecting to mention the lack of a contingency plan. Italy enacted similar restrictions and ramped-up inspections in August, at “first alarm” of cholera spreading within its borders, blaming the outbreak on a roving band of “gypsies” whom they claimed brought cholera with them from Russia. Italy’s aggressive measures worked; fortunately, they managed to stop the spread of the deadly waterborne disease in its tracks.

Exactly three weeks after departing Palermo, on the morning of Saturday, October 8, 1910, the Liguria delicately glided into her familiar spot at the Northeastern Fruit Wharf. The press would report this as the moment of the ship’s arrival, but the Liguria had been in town for a full day already, anchoring midstream at Algiers Point on the West Bank in the early morning of Friday the seventh. First-class passengers had been permitted to disembark immediately—no detention necessary—and were shuttled in tug boats to the foot of Canal Street. Meanwhile, medical examiners from the Marine Hospital climbed aboard and spent the entire day shadowing the ship’s physician as he screened the passengers in steerage for cholera and other illnesses. That night, they gave the ship the all-clear.

“Very little sleep was indulged by anyone on board, as the immigrants, now that they were at last with the confines of ‘that great America’, could not rest, but sat up discussing the life before them,” the Item reported.

For Luigia, alone with her eight-month-old son in their private cabin on the deck above, that night— for the first time in nearly three weeks—there was quietude and calm and, at long last, sleep.

In just two years, Italy would be at war in Tripoli against the Ottoman Empire, and the Italian Line would be forced to suspend all business and be ordered back home. Nearly all of the line’s steamships were commandeered and retrofitted for combat. But not the Liguria. She was sold to the Russian Steam Navigation and Trade Company, rechristened the Apho, and delivered to Odesa in Imperial Russia. After the regicide of Czar Nicholas II and the ghastly murders of his entire family, the old steamship spent her twilight years chauffeuring Bolsheviks around the Black Sea, an ocean liner that retired to become a sea ferry.

Decades later, whenever Louise Marcello recalled the story of her arrival in America, she rarely mentioned the ironies or the indignities of that morning, how, for example, a New Orleans police detective, John D’Antonio, interrogated passengers, the way she’d been patronized by some of the men on board and made to feel stupid by a smug immigration officer for speaking broken English. He didn’t know that she was a polyglot or that English, which Louise soon mastered, would be the seventh language she spoke fluently. “The questions asked by the officials are astonishing,” one of the ship’s passengers, identified only as an Italian girl, told The Daily Picayune. “They not only want to know whether you can support yourself, but whether you can support your ma and your grandma. The questions are something else.”

Louise would never forget the scene at the wharf that morning, October 9, 1910. It was as if half of Sicily had shown up to welcome them, thousands of people, the women dressed in reds and blues and pinks and yellows and the men in corduroys and velveteens, a parade of euphoric joy and, above all, profound relief.

“The examination over, the immigrants were free to join friends outside the (inspection) shed, and were compelled to force their way through a solid mass of humanity that packed the doors. Policemen were obliged to clear a passage, and as one, two, or a dozen of the immigrants reached the door, they were hailed by someone who grabbed the baggage, hustled it to one side where it was put on the ground for the moment, and then followed by several minutes of audible kissing. Embraces were around and around, to all of the family and then some. All talked at once, yet all seemed satisfied to have it so,” the New Orleans Item reported.

Louise also never forgot the moment she locked eyes with her husband Joe, the then-27-year-old Giuseppe Minacori, whom she hadn’t seen since he departed Tunisia more than a year ago, his eyes welling with tears and her belly, unbeknownst to either of them, already swollen with their child. He left Tunis on a ferry back to Sicily, the first leg of his voyage from North Africa to New Orleans, aboard Captain Anfosso’s ship. Nor would she ever forget the moment Joe first met their son and how in that instant they were the happiest they ever had been before or ever would be again.

“While there was nothing intensely exciting about the landing of the steamship Liguria at the Northeastern Fruit Wharf yesterday,” the Daily Picayune reported:

“[T]here was enough room to make the occasion interesting and rub off the cold routine of the business conducted by the United States officials…. The waves of the immigrants were in bundles, trunks, bags, chests, and hand satchels. Huddled around the baggage were men, women, and children. The children romped up and down the wharf and gave their fathers and mothers no end to worry, absolutely oblivious to the fact their parents had landed in a strange land…. It was stated by all that the class of immigrants was also above the average. Some of the women and many of the children were marked types of Italian beauties. From Southern Italy were the olive-complexioned women and from the northern points were many handsome blondes. So beautiful and fine-mannered were many of the children whose parents had quarters in the steerage that they were taken charge by first-class passengers during daylight hours on the voyage and given the gala time of their lives.”

More than anything else, Louise Marcello—the matriarch of a sprawling and powerful American family—remembered that the night before she stepped foot on American soil, with her baby cradled in her arms, they slept peacefully in their very own cabin.

Joe’s older brother had kept his word, guaranteeing that mother and child were delivered to him in New Orleans. Louise’s brother came as well, which was only fitting. Both brothers shared the same name, the name Giuseppe and Luigia gave their son: Calogero.

The ship’s passenger manifest, along with an affidavit sworn before Immigration Officer Daniel Trazinuki from the Italian physician responsible for conducting personal examinations of all of those on board, provided descriptions of all four family members:

149. Calogero Minacori, 35 years old, male, 5’4”, dark complexion, chestnut eyes and hair, not able to read and write, not a polygamist or anarchist, married to Angela Gallo in Tunisia, born in Ravanusa, Girgenti, a citizen of Italy, last residence in Tunis, Africa, carrying $25 in cash, joining brother Giuseppe, no ticket but passage paid;

150. Calogero Farruggia, 29 years old, male, 5’2”, rosy complexion, chestnut eyes and hair, not able to read and write, not a polygamist or anarchist, married to Lucia Zera in Tunisia, born in Ravanusa, Girgenti, a citizen of Italy, last residence in Tunis, Africa, visiting his brother-in-law Giuseppe, carrying $25 in cash, no ticket but passage paid;

151. Luigia Farruggia, 17 years old, female, 5’3”, rosy complexion, chestnut eyes and hair, a married housewife, able to read and write, not a polygamist or anarchist, born in Ravanusa, Girgenti, a citizen of Italy, last residence in Tunis, Africa, nearest relative is her mother Maria Cervini, joining her husband Giuseppe Minacori, carrying $10 in cash, passage paid by her husband; and

152. Calogero Minacori, six months old, male…(other details duplicate his mother’s information).

Notably, baby Calogero was eight months old, not six, a discrepancy that would become relevant much later, manipulated to discredit and obscure the inconvenient fact that he was born in a country that no longer existed.

So, how do you explain the mistake? Well, considering the remainder of the infant’s entry was obviously copied from the one written directly above describing Luigia (resulting in the dubious claim that the newborn is able to read and write), we can infer the ship’s physician, likely after examining the boy’s mother and finding her to be healthy, was satisfied the infant posed no risk of spreading disease or infection and, perhaps in the interest of time, simply moved to the next passenger in line. It’s also worth noting that the manifest provided only passengers’ ages, not their dates of birth. The boy’s birthday, however, does appear on the only other contemporaneous record specifically identifying him during his first year of life, his baptismal record, and there is no reason whatsoever to question that document’s authenticity or its provenance.

The manifest does contain one mystery at least, though. The handwritten entries for baby Calogero and his family are all legibly written, but for some reason, there’s a deep line scrawled across the name of his paternal uncle, the 35-year-old Calogero Minacori. The line is prominent enough that when the manifest was finally transcribed in 2003 by members of the Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild, it earned a mention in the transcriber’s notes. Unfortunately, the Liguria’s passenger manifest is the only record documenting the presence of Giuseppe Minacori’s older brother in the United States. What happened? Why was his name crossed out?

The city’s newspapers had exhaustively reported the ship’s arrival in October 1910. There were, for example, multiple stories about how New Orleans Detective John D’Antonio and Officer T.P. Simone boarded the Liguria, spent several hours grilling passengers about the Black Hand and the Mafia, and “did not find a person with a suspicious record.” So, if Uncle Calogero Minacori was forced to return home, it wasn’t because he was a convicted criminal or suspected of being in the Black Hand. We also know that at least a couple of passengers were denied entry.

Reporters were especially taken with the plight of a charismatic 15-year-old runaway named Maggio Ignacio, who, despite not knowing a word of English, managed to charm immigration officials and crew members. “Maggio is admitted by the inspectors to be one of the brightest lads (who) ever entered this port as an immigrant,” the Item claimed. In the end, though, the rules were the rules, and poor Maggio was deported back to his parents in Sicily.

At some point, Uncle Calogero went back as well, and while the circumstances of his return trip remain unclear, there’s compelling evidence that suggests he never even stepped foot on American soil at all. According to an Italian writer who spent time in Ravanusa in 2012 interviewing members of the Minacori family, the family folklore holds that Guiseppe’s brother had contracted an eye infection and was ordered to return. There is at least some circumstantial evidence that seems to support the story.

Five days after the Liguria’s physician finished examining all of the passengers in steerage, including 35-year-old Calogero, whose name the doctor, presumably, then crossed out, the Daily Picayune reported the “work of discharging passengers… was practically completed yesterday, when the United States Immigration Bureau, in most instances, took bonds for the release of passengers who had been held pending investigations.” The paper failed to mention the number of people being detained, but the report noted that at least “one of two cases of trachoma, a serious affliction of the eyes, were discovered” among the ship’s passengers.

It would take nearly 42 more years before Giuseppe, now an American citizen named Joseph, and his older brother Calogero were reunited. The steamships shuttling people between New Orleans and Palermo had stopped running decades ago—the boats were either garrisoned into two world wars or sold to the Soviets—so he’d sailed from New York instead, accompanied by his wife, who, a lifetime before, had been a teenager named Luigia, and their first-born granddaughter, a teenager gifted with the name that she made for herself in America, Louise.

The Marcellos weren’t in Sicily more than a week before Joe contracted bronchopneumonia and was rushed to the Hospital Feliciussa in Palermo. There, on the island of his birth and the soil of his ancestors, on June 17, 1952 at 3:10 p.m., with his two Louises and his big brother Calogero by his bedside, Joseph Marcello died. He was 69.

The saga of Carlos Marcello, the legendary Mafia boss who ruled the New Orleans underworld for more than 40 years, began on a mild, cloudy day in October of 1910 at the Northeastern Fruit Wharf in a city he would one day conquer and in a country he would always claim, even if it never claimed him.

As his 35-year-old uncle, Calogero Minacori, prohibited from entering the United States, languished aboard the steamship and awaited the inevitable order for his deportation, the other Calogero Minacori, an eight-month-old baby, was being carried from a first-class cabin and into the capital city of his future empire.