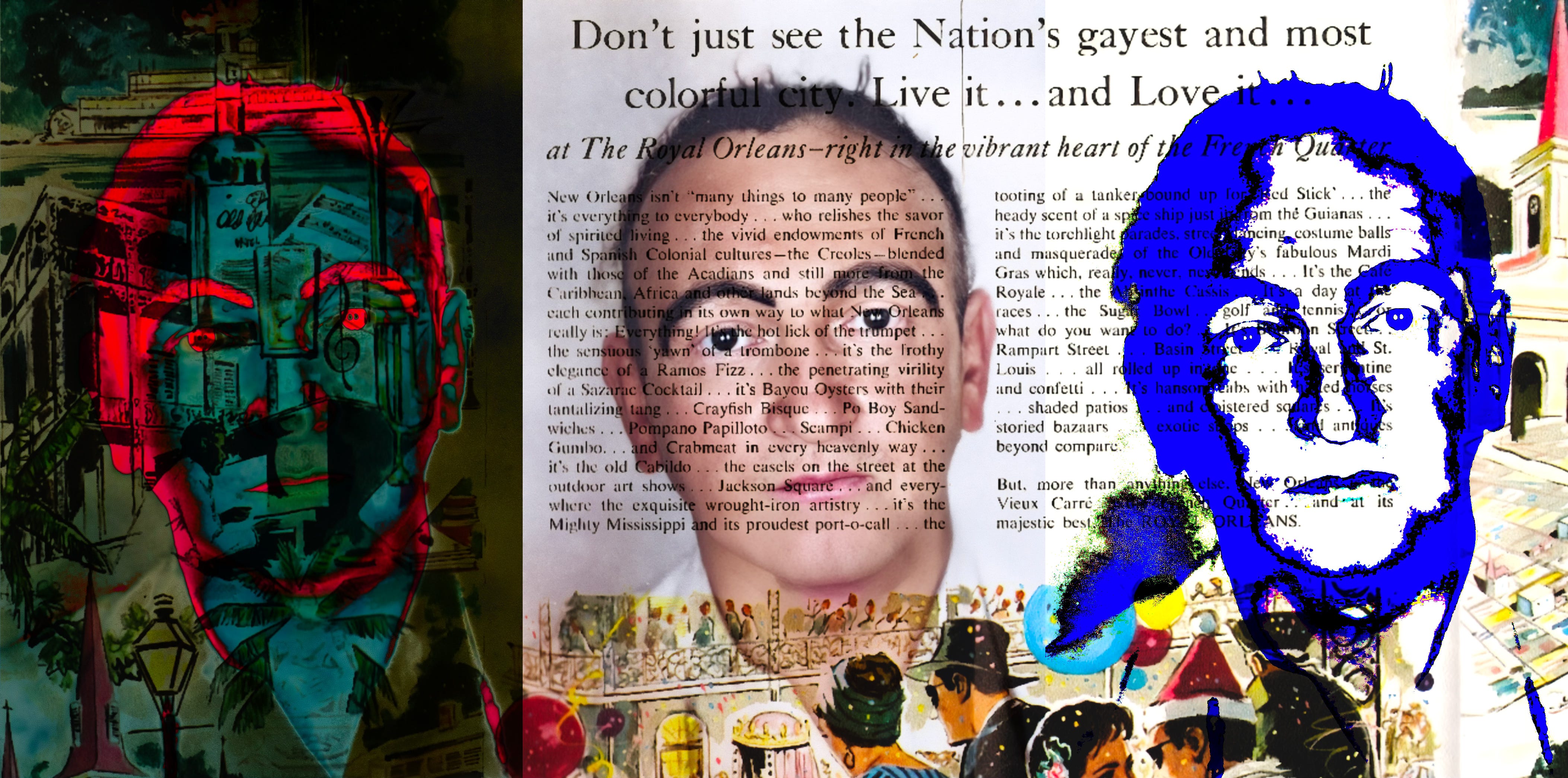

Clipping Ferrie's Wings

Mental cures, moral panics, and the improbable afterlife of David Ferrie.

Part Two of a two-part series. Read Part One here.

I.

“People today are too concerned with trivial matters, things that could be dismissed if viewed in the light of the bearing on the eternal,” Dave Ferrie, a pilot with Eastern Airlines and self-described psychologist, told an audience of 75 Alabama businesswomen at Birmingham’s Episcopal Church of the Advent on December 1, 1954.1 “What has worry over everyday things have to do with eternity?”

The Birmingham News published a brief item about Ferrie’s lecture at the historic downtown church the following day. “Capt. Ferrie reported a tremendous increase in mental illness cases in the United States,” the paper noted. “He attributed the increase to two things: ‘The lack of parental and teacher discipline, and underdeveloped willpower.’ He said most mental illnesses can be cured through the patient’s will to be cured.”

David William Ferrie’s life serves as a vivid reflection of how mid-century America dealt with those who deviated from the n…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Imagine Louisiana to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.