On Its 20th Anniversary, the Truth About the Collosal Failure of Trump Tower New Orleans

Four days before Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, Donald Trump announced plans for a $400 million skyscraper, the tallest in Louisiana. But the reality TV star was really a paid salesman.

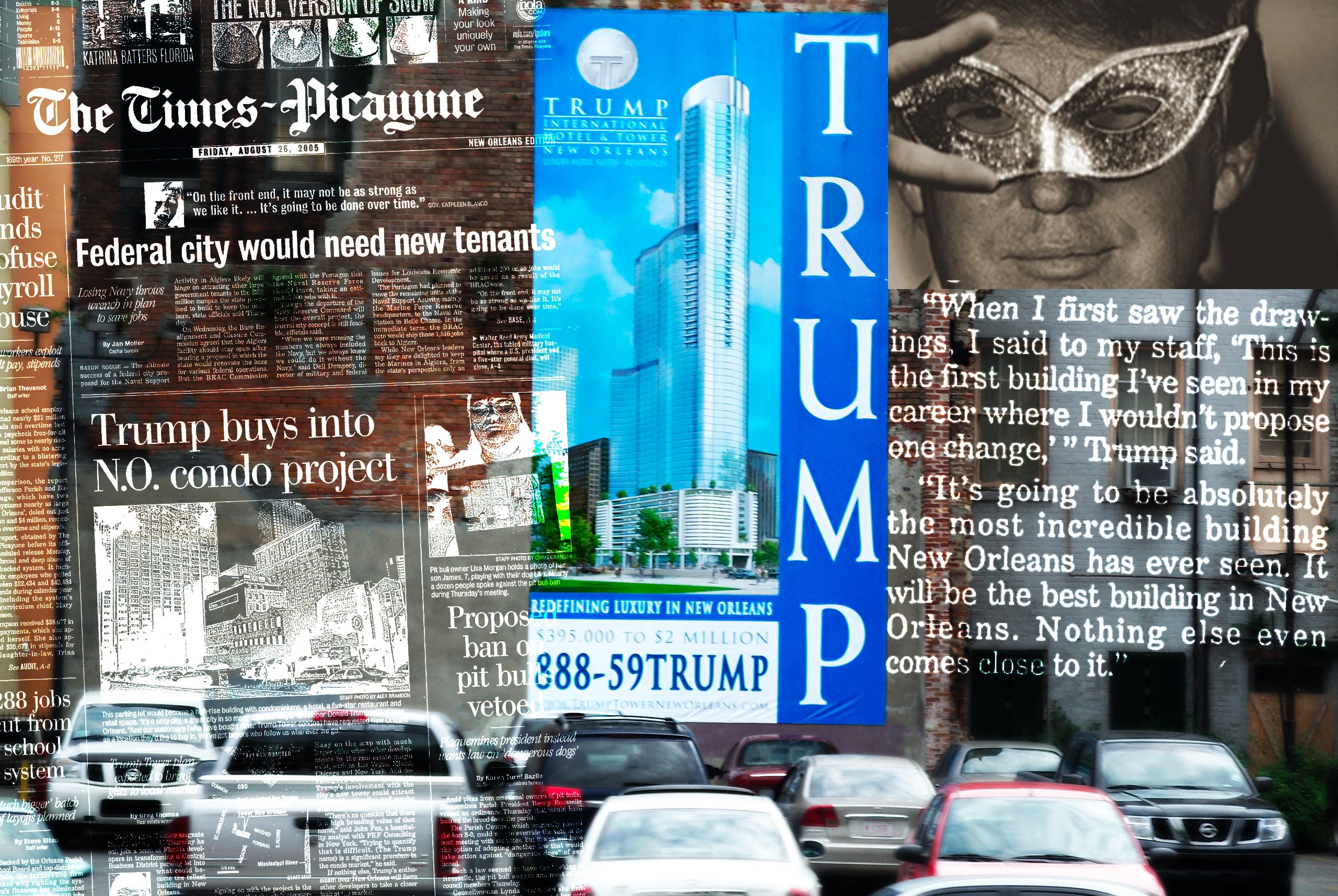

On Friday, August 26, 2005, the front page of the Times-Picayune carried huuuge news for New Orleans: The day before, from the cheaply-gilded offices atop his epoynmous tower in Midtown Manhattan, Donald Trump, star of NBC’s newest hit reality television show, “The Apprentice,” announced he was stamping his name on a massive new skyscraper in the heart of the city’s Central Business District, located on the site of a parking lot at 501 Poydras Street.

“It’s a sexy, great city in so many different ways, and our customers have requested New Orleans as a location they’d like to buy in,” Trump claimed. “We’ve got buyers who follow us wherever we go.” According to the Times-Picayune, Trump’s plan was “expected to bring glitz” (whatever that meant) to a city already internationally known for its spectacular architecture. “[Trump Tower New Orleans] is going to be absolutely the most incredible building New Orleans has ever seen,” he boasted. “It will be the best building in New Orleans. Nothing else even comes close to it.”

News of Trump’s involvement effectively relaunched the same proposed development that had been publicly announced three months earlier. Initially marketed as a $120 million, 50-story, 500-unit condominium building, with Trump aboard, the development was now being described, confusingly, as a $400 million, 70-story building, which would carry the name and the flag of “Trump International Hotel and Tower,” even though it was still “a condominum project.”

Construction was expected to begin in eight months, and the entire development would be privately financed.

Mayor Ray Nagin was ecstatic, arguing that Trump’s imprimatur was proof that the city’s real estate market was on the upswing. “This is international news,” he declared.

That day, buried on page ten, the Times-Picayune ran a brief report about a tropical storm that had strengthened into a hurricane two hours before reaching Florida’s Atlantic Coast.

Three days later, at approximately 6:10 a.m., Hurricane Katrina made landfall in Buras, Louisiana, a tiny fishing village 60 miles south of New Orleans on the frontier of the Mississippi River’s byzantium bird’s foot delta. By the day’s end, after the storm had passed and just as New Orleans began to breathe a sigh of relief that it had been largely spared, the city’s worst fears were realized when the catastrophic failure of the federal levee system put 80% of New Orleans underwater.

Although Hurricane Katrina would later be blamed for destroying the dream of Trump Tower New Orleans, the proposed development endured after the storm for nearly five years. In early 2006, Trump claimed to have taken reservations or deposits for roughly 175 units, accounting for more than 40% of the entire development. A year later, on March 15, 2007, the New Orleans City Council unanimously approved the Trump Tower plans, clearing the final regulatory hurdle.

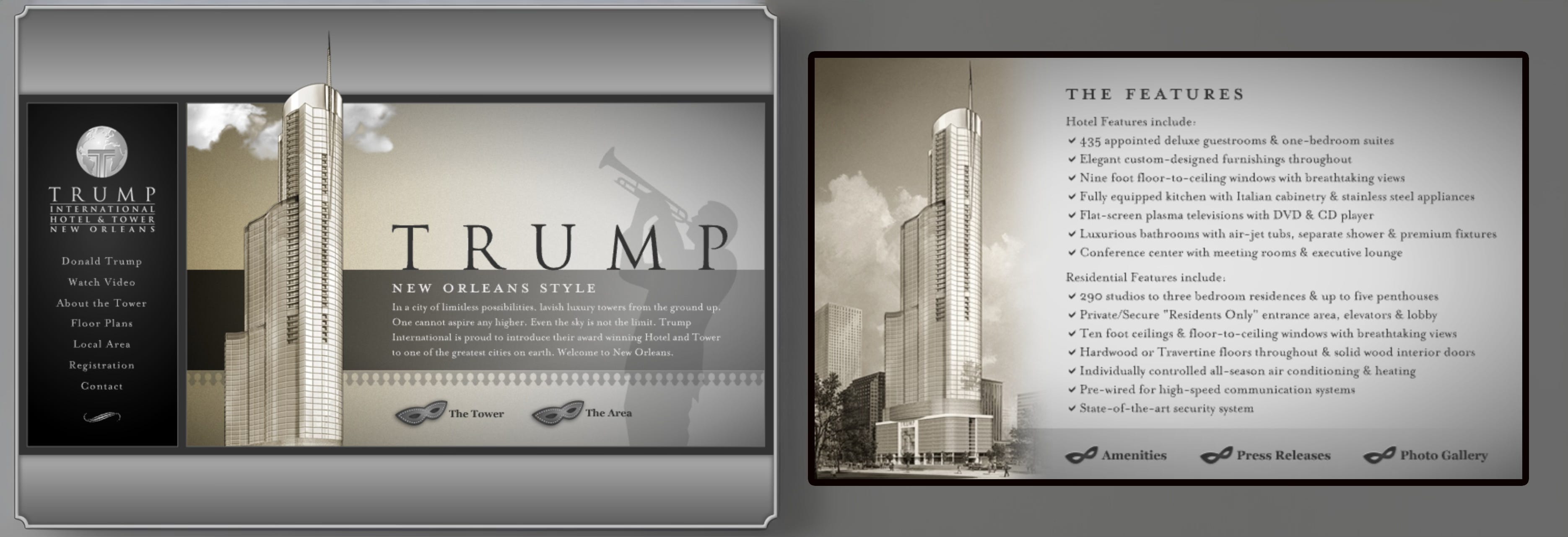

The finalized plan called for an 842-foot tower (716-feet without the spire)—not only the tallest in Louisiana, but also taller than anything outside of Houston on the entire Gulf Coast—comprised of 734 units, 290 traditional condominiums and 435 “condotel” rooms, which would be sold individually but allowed to operate collectively as hotel rooms. Once constructed, the building would dominate the skyline of a city left fallow by the storm.

There were other tangible signs of progress: At the site of the proposed tower, a giant sign advertising the project; a slickly designed website, TrumpTowerNewOrleans.com, featuring a video testimonial from the Donald himself, and the opening of a small sales office in New Orleans.

In many ways, the story of the planned skyscraper isn’t about the collateral damage left in the wake of a devastating hurricane; it’s about a remarkably durable, wildly ambitious, and stupidly gigantic project that, at its core, was defined by deceiving the public and buyers. It’s about a fake news story that was manufactured 20 years ago with the hope of making a quick fortune by selling a few hundred overpriced condos. It’s about a starstruck and overstretched local media, a corrupt and incompetent local government, and the misplaced priorities that some placed in a city struggling to recover and rebuild.

In March of 2008, WDSU’s Ken Jones came closer than anyone else in reporting the truth by inserting an unconfirmed rumor into a story that otherwise would have just been disinformation from the Trump team about their plans to break ground in the summer and how they have been “exceeding condo presale estimates by 300%, so far,” whatever that meant.

“There’s been talk that the only connection Donald Trump will have with this project is his name,” Jones dished. He then asked Christian Moises of New Orleans City Business Magazine, ostensibly an expert in the city’s business news, if he could clarify Trump’s role in the project, and Moises started responding before realizing that his answer was also vague and confusing.

Donald Trump wasn’t the developer, or even a co-developer, of the proposed tower in New Orleans that carried his name. He wasn’t attracted to the project as an investor. His interest in the project wasn’t the result of methodical scrutiny or anything resembling due diligence. Despite the headline of the Times-Picayune, “Trump buys into N.O. condo project,” Donald Trump wasn’t buying anything in New Orleans. Trump didn’t spend a dime of his own money on the project. He’d entered into a licensing agreement with the project’s real developers, wherein he was paid upfront for use of the Trump brand and for his involvement in publicizing and marketing the project, which hinged entirely on substantial pre-construction sales.

With Trump as their hypeman, the developers reintroduced their plan to the public with the hope of generating the enthusiasm and interest necessary to lure in enough early buyers—and cash—to secure a construction loan. If the project succeeded, Trump also stood to gain on the backend in hotel management and brand licensing fees. If it failed, his only risk was reputational, a risk in every transaction. Although the plan never materialized, Trump nonetheless earned significant goodwill for the decision to continue pursuing the deal in the years following Hurricane Katrina. Indeed, according to a recent report by Rolling Stone, Trump may have been the only person who made money from the arrested development. Aside from the purchase of prime real estate on Poydras, Trump’s $2 million licensing fee was easily the largest single expense associated with the proposal. In hindsight, it also may have doomed the project from the very beginning.

Four days before Hurricane Katrina, Trump’s first act as the development’s paid spokesperson was to add 20 stories to what had been conceived as a 50-story building. Days later, however, in the immediate aftermath of Katrina, the worst natural disaster in American history and an unprecedented humanitarian crisis, he was working behind the scenes on a plan to evacuate New Orleans and rescue the Trump brand from catastrophe. In a 2010 deposition, Trump revealed that he offered to return his licensing fee to the developers shortly after Katrina, with the intention of walking away from a project that had been announced just days earlier. His offer, however, was rebuffed. Henceforth, his son Don, Jr. would be the point person on the project.

In early September, 27-year-old Donald Trump, Jr., reaffirmed his family’s commitment to the colossal development in New Orleans. “We're in this with you guys,” he said. “But our sentiment right now is that it's inappropriate to talk business (at a time) with such a great loss of life.”1

In late November 2005, the Trump Organization finally issued a formal statement expressing confidence in the city’s recovery, which the local media would pathetically attempt to attribute as a direct quote from the Donald himself:

The Trump organization stands behind the people of New Orleans as they rebuild their great city. We have no doubt that the city of New Orleans will come back stronger than ever, and the Trump organization is proud to be a part of this redevelopment process as New Orleans gets back on its feet. Our decision to enter the New Orleans market has only been reinforced by the dynamic nature and resilient strength of the people of New Orleans.

“Tower could power N.O. revival,” the Times-Picayune asserted in a front-page report on November 21. The press essentially treated Trump’s proposed skyscraper as if the future of New Orleans depended on its swift completion, a sentiment that seemed to be shared by the city’s director of economic development, Don Hutchinson, and Michael Olivier, secretary of Louisiana Economic Development. Both men supported providing lucrative tax incentives to entice people to buy Trump-branded luxury condominiums, an obscene example of the worst kind of disaster capitalism. Specifically, they hoped to persuade Congress to allow condominium buyers the ability to deduct half of the unit’s purchase price from their federal income taxes.

“The message to the world is that a major project reflects confidence and security for investment,” Olivier stated. Hutchinson compared the incentives for Trump to the issuance of $8 billion in so-called Liberty bonds in the wake of the September 11th attacks. “The way I see it, what Congress did for New York is good enough for New Orleans. For [Trump tower in New Orleans] to start within six months would send a critical message,” said Hutchinson. “It will tell other investors to take a second look.”

Donald Trump tried and failed to cheat his way into a previous deal in Louisiana more than a decade earlier. In the summer of 1993, Trump flew his oversized private jet to Baton Rouge and stomped over to the Governor’s Mansion to ask Edwin Edwards to rig the rules and extend the deadline for applications from casino operators. Trump learned too late of Louisiana’s plans to grant 15 casino licenses, 14 operating on riverboats and one on land, at the foot of Canal Street in New Orleans, and he hoped his charm offensive would persuade the governor to grant him mercy. He really wanted one of those riverboats, and he was certain that his application, once submitted, would easily win on its own merits. Edwards was amused but unmoved. Trump would fly back home to New York, soured and slighted.2

New Orleans never sought out Donald Trump,3 and even before Katrina, it wasn’t clear if there was really a market for the kind of development he was proposing: Small but tall luxury condominiums in a newly constructed building that looked like it belonged in Dubai or Singapore or, well, anywhere in Florida. The architectural firm responsible for its design were, unsurprisingly, based in Fort Lauderdale and, if their website portfolio is to be trusted, apparently responsible for designing a significant number of the monstrous high-rise condominium buildings that are cluttered along Florida’s Atlantic Coast and sold to wealthy Yankees whose idea of a luxury beach vacation involves looking down at a crowded beach whenever they aren’t on a crowded beach. Wealthy Louisianians built Destin, and when it became too crowded, they moved down to the New Urbanist utopia that wealthy families from Alabama and Arkansas built along 30-A.

It would take more than a decade before anyone could fully appreciate the details of Trump’s licensing agreements or the scale of his public deception. While the planned development in New Orleans languished, Trump licensed his brand for similar proposed projects in Philadelphia, Phoenix, Charlotte, and Tampa, all attempting to sell condominiums under the guise of Trump’s name, and all failed to make it to construction. In 2009, Trump’s name was removed from a proposed “condotel” in Fort Lauderdale that defaulted; it would eventually materialize as a Conrad hotel, a flag of the Hilton chain, in 2017. Domestically, projects that paid to license the Trump brand were more likely to fail than succeed; the brand would find more success overseas.

In 1999, Trump signed his first licensing agreement with the South Korean conglomerate Daewoo for a high-rise condo development in Seoul named Trump World. Two years later, in December 2001, Michael Dezer, an Israeli immigrant who arrived in New York as a teenager and made a fortune in real estate, paid Donald Trump to license his name for a massive, 11-acre development on Sunny Isles Beach in Miami. “I saw that Trump was a better name than Dezer,” Dezer told the Miami Herald in a notably candid interview in 2002. “The Trump name is magic.” Dezer never attempted to conceal the fact that he paid for the Trump brand. Today, Donald Trump’s first licensing agreement development in the United States, Trump Grande on Sunny Isles Beach, is a complex of three enormous high-rises: Trump International Beach Hotel, a “condotel” managed by Sonesta, and a pair of 55-story condo buildings, Trump Palace and Trump Royale. But despite its success, Trump Grande would also prove to be a magic trick difficult to perform outside of Miami.

Why would anyone pay Donald Trump millions of dollars to pretend he liked the condos they were selling in New Orleans? Why didn’t the press warn the public of a fraud that now looks so obvious?

Twenty years ago, when the tabloid billionaire in command of his family’s real estate empire decided to stamp his name on a building, there was an implicit understanding that the building belonged to him. Even though his career was beset by a series of spectacular, vainglorious failures and his wealth was inherited and nearly squandered, by 2005, Donald Trump had been “resurrected as an icon of American success,” reinvented completely by the same television producer who gifted the world with Survivor, a show that recently wrapped up filming its 50th season, and turned into the megawatt lucky star of The Apprentice. Two years earlier, Donald Trump was a blubbering, washed-up, 1980s D-list celebrity, instantly recognizable but rendered obsolete by societal advancements, an artifact of a different era. His transformation on the silver screen had been so swift, so convincing, so complete, it was possible to forget the person who existed before he was replaced on television; even the term “real Donald Trump” had been reappropriated.

“I was seriously in trouble,” Trump confessed during the opening credits of The Apprentice on January 8, 2004. “I was billions of dollars in debt. But I fought back, and I won, big league.”

“What was he saying?” America asked. “Big league? Or bigly? Is bigly even a word? Either way, Trump, what a character!”

To be sure, there were plenty of people who called bullshit on the version of Trump that Mark Burnett curated for television, and in New Orleans, there was ample skepticism about the legitimacy of his plans and little evidence of the value that his name was supposedly adding. But 2005 was a lifetime ago, and given the timing of Trump’s announcement, there were plenty of other things that deserved priority over a billionaire’s plans to sell condos to dumb, rich people.

Unbeknownst to the public, the real developers of the building proposed at 501 Poydras Street were a consortium out of Pensacola, Florida, the same small group of investors—namely, Robert Rinke and brothers Allen and Fred Levin—who had courted controversy and invited conspiracy by transforming an unspoiled, 28-acre stretch of gorgeous beachfront property on Santa Rosa Island at the eastern end of Pensacola Beach into a gargantuan luxury resort community of high-rise condominium buildings they named Portofino. In New Orleans, the brothers Levin and Rinke added another, less notorious Pensacolan, Cliff Mowe, to their roster. Before recruiting Trump, Mowe was primarily responsible for handling the press. Notably, when the project was first announced, Jim Haslett, the head coach of the New Orleans Saints and the owner of a condo at Portofino, was named as a minority investor, with a 4% equity stake. Haslett was fired from the Saints at the end of 2005, following an abysmal 3-13 season, and his name subsequently disappeared from the project’s promotions.

Portofino’s story provides the backstory for the New Orleans venture, as success in Pensacola emboldened the same team to try a Trump-branded tower later.

Announced in 1997, the original plan called for five condominium towers, each roughly 21 stories tall with 150 units, totaling about 750 luxury condos. At the time, such height and scale were unprecedented on the Florida Panhandle coast. The Portofino towers would become the tallest buildings on the Gulf Coast between New Orleans and Tampa. The Levins, who grew up in Pensacola Beach, were not sentimental about the sleepy, low-rise beach town of their youth. They watched jealously as a parade of beachfront high-rises began marching down the Atlantic Coast and made landowners into developers and developers into billionaires. They wanted to do that on the land they controlled along Florida’s Forgotten Coast.

Portofino’s site, though beautiful, was environmentally sensitive. Of the 28 acres slated for development on Santa Rosa Island, about 11 acres were wetlands and marshes teeming with saltwater grasses vital to the Pensacola Bay ecosystem. These wetlands filtered water flowing into Santa Rosa Sound and provided habitat for fish and wildlife. The developers’ plan, however, treated these marshes as expendable “unsightly” swamps in the way of their vision. In 1998, the developers applied to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for a permit under Section 404 of the Clean Water Act to fill in over half of the wetlands on the site. Specifically, they sought permission to dump fill into 6.5 acres of marsh (out of 11) to create solid ground for the towers and infrastructure. This request immediately triggered opposition from multiple fronts: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Environmental Protection Agency, and NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service all filed strong objections. Residents and environmental advocates were outraged. But the Levin group pressed forward, countering the objections with promises of mitigation and using their political influence where possible. Ultimately, in August 2000, the Army Corps of Engineers approved the Portofino permit, mainly on the developer’s terms. Two small wetland areas would be untouched as a token preservation, and the developers were responsible for creating 6.5 acres of artificial marshes off-site to offset those destroyed by the project’s construction. (In 2004, Hurricane Ivan destroyed some of the mitigation areas, which the Corps deemed as an “Act of God” rather than holding the developers responsible.) Notably, the Corps approval occurred without a public hearing, and even more strikingly, the Corps’ Florida commander, Col. Joe Miller, signed the permit and simultaneously issued letters to the objecting residents stating that no hearing would be held; the next day, Miller retired.

Portofino’s construction proceeded soon after permit approval. The project broke ground in 2001, and by 2004, the first towers were completed and units sold. Ultimately, five towers were built in the initial phase (each about 20 stories, with a total of roughly 700+ condos). The resort opened its spa, restaurants, and beach club, attracting vacationers and second-home owners. Portofino became a success financially, selling out units during the mid-2000s real estate boom. But plans to build two more buildings, the final phase of the development, stalled after the market crashed. And by the time the market recovered, the pandemic happened. At least that was the excuse. Eight years after announcing the final phase, although Levin-Rinke Realty still operates the website promoting the pre-construction sales of units at Building 6, Allen and Fred Levin have both passed away, and the project is still on hold.

But in 2005, the dream was still very much alive. Flush with cash from Portofino’s success, buoyed by confidence after the construction of its first buildings, and buttressed by Fred Levin’s personal fortune, the Pensacola developers looked three hours west for their next project. After Katrina, they could afford to wait and to pay for Trump’s patience.

But why this project? Why was Fred Levin spending his fortune to arrange a marriage between Donald Trump and New Orleans? Who exactly was Fred Levin, and how did he make his fortune?

One of the most consequential and financially successful trial lawyers in American history, until his death at the age of 83 in 2021, Fredric Gerson Levin had been the wealthiest, most influential, and most recognizable person in the Florida panhandle for nearly 30 years. During the 1990s, he was also considered by many as the most bombastic, divisive, and offensive figure in the entire state, which, in Florida, is a distinction that requires more personality and chutzpah than anywhere else.

Levin is best known for engineering Florida’s landmark $13 billion settlement from Big Tobacco in 1993 by convincing his friend, state Senate President W.D. Childers, and Gov. Lawton Chiles to pass and enact the Third Party Medicaid Liability Recovery Act. “I was at Whistler, in British Columbia, sitting in the bar smoking a cigarette, having a drink, and [prominent Charleston, South Carolina trial lawyer] Ron Motley comes up to me and says, ‘How would you like to handle a tobacco case in Florida?’” he recalled to the Florida Super Lawyers Magazine in 2006. “I reached for a statute book, and it opened up to this thing on Medicaid. I started reading it and thought, ‘You know, I could change a few words in this statute and it would be perfect for a tobacco case.’”

Because of the change, in 1998, Levin personally earned $51 million from the Florida settlement, and because of his involvement in similar lawsuits in other states, he eventually took home an additional $129 million. Levin’s entire haul from Big Tobacco was the equivalent of $358 million in today’s dollars. Although his net worth was never disclosed, considering his share of the tobacco earnings and the scale of his philanthropy (totaling at least $75 million, including $40 million bequeathed by his estate to the University of Florida’s Levin College of Law in 2021), he was likely worth hundreds of millions of dollars when the proposed development in New Orleans was announced in 2005.4

But why did a liberal, Jewish trial lawyer and Democratic Party megadonor seek out Donald Trump? Curiously, Young’s 2014 biography doesn’t include anything about Fred Levin’s work with his brother Allen on Portofino or on Trump Tower New Orleans, but it does reveal that the two men already knew each other. They first met in the mid-90s, when Trump was still in the casino business and Levin worked as a boxing promoter for Pensacola native Roy Jones, Jr. One year, Trump invited Levin to his birthday party and told him to bring as many people as he wanted. (Edwin Edwards also earned invitations to Trump’s parties.) They were friendly with one another. That helped. It’s also worth reiterating that the Donald Trump of today wasn’t the Donald Trump that Levin knew, a man who could have also been characterized as a Democratic Party megadonor.

The two men were both wealthy, iconoclastic, controversial, flamboyant, vulgar, and combative. They both trafficked in tabloid gossip—Levin claimed the National Enquirer as his favorite paper—and, as evidenced by the five high-rises of Portofino and the planned skyscraper in New Orleans, they shared a similar aesthetic.

Levin sought Trump’s help with his proposed development in New Orleans, a move that was arguably misguided from the outset, as he genuinely believed Trump had the expertise and cachet needed to sell a project of this scale. And in 2005, very few people would have disagreed.

Fred Levin passed away from COVID-19 on January 12, 2021, six days after the January 6th attacks at the Capitol, eight days before Joe Biden moved into the White House and Trump moved to Florida. A year later, Pensacola named a street in his honor. On a Sunday morning, hundreds of people showed up to celebrate the inaugural Fred Levin Way Festival and to express appreciation for all of the ways Fred Levin contributed to the city. His final remarks, printed in his obituary, were an urgent warning that would have been politically controversial in the Florida panhandle, a place that had just reelected Matt Gaetz to another term in Congress. “PLEASE EVERYONE, JUST WEAR A MASK! It’s not too much to ask. It makes the difference of saving a life or taking a life.” Levin made only a few public comments about his involvement in the Trump Tower proposal in New Orleans and even fewer about his opinion of Trump. That would have been bad for business. But there’s no doubt he loathed Donald Trump as president and would have never associated himself with the Trump brand in 2005 had he known how toxic it would become in 2015.

Levin and his team of Pensacola boys signed a contract with Donald Trump, paying him to serve as their dealmaker and promising to give him all the glory. Hurricane Katrina disrupted their timeline and created uncertainty, but it also provided an enormous infusion of resources and goodwill that could have been utilized creatively. In late 2007, for example, Poydras Properties Hotel Holdings, a group of investors from Los Angeles, purchased the shuttered 1,193-room Hyatt hotel next to the Superdome from Chicago-based Strategic Hotels & Resorts for $32 million. The hotel had been heavily damaged and needed upwards of $250 million in renovations. A year and a half later, in February 2009, the Louisiana State Bond Commission approved the sale of $225 million in special low-cost Gulf Opportunity Zone (GO-Zone) bonds for the project. The renovated hotel reopened to the public in October 2011, and in 2019, Poydras Properties sold the hotel to a local partnership including Saints owner Gayle Benson, developer Darryl Berger, and Dr. Eric George, a hand surgeon and investor, for $400 million. Even though the residential real estate market had changed dramatically after Katrina and despite the overwhelming evidence of a lack of demand for a 70-story, 734-unit building, Trump never altered from the plans that were already too grandiose before the storm.

If there was a silver lining to the decision to reject Donald Trump’s offer to return the $2 million he was paid to license his name for the proposed development in New Orleans, it was that Fred Levin had forced Trump to remain accountable to the terms of their agreement and, unwittingly, helped to expose his licensing agreement scam.

Fred Levin lost at least a couple of million dollars on the project, but Donald Trump was responsible for its failure.

Epilogue

When folk singer Arlo Guthrie, the son of legendary musician Woodie Guthrie, arrived in New Orleans via Amtrak in early December 2005, he warned against the possibility of rebuilding a “Disney-fied” destination.

“Nothing wrong with Disney,” Guthrie said, “I work with them all the time. But there's a place for everybody, and they don't need to be in New Orleans. It doesn't need to be time shares or owned by Donald Trump. That's probably what will happen unless people can get back to their apartments and houses as soon as possible. The best way to defend against an oncoming cultural disaster is to get the music going and the food cooking and the people walking around. Get the people back into the city who were living there all along. The uniqueness of New Orleans depends on the people themselves. And it's not good enough just having some other people; it has to be those people."

On July 27, 2011, the Poydras Street land was foreclosed upon and sold at a sheriff’s auction. Its new owner was a local who knew precisely what to do with the property. Today, 501 Poydras Street is restored to its former glory, as a forgettable parking lot next to a busy intersection.

Sources:

The Times-Picayune archived reports (2005-2011) on Trump Tower N.O. announcement, approval, delays, and cancellation.

Curbed New Orleans 2015 retrospective on the project’s demise.

Associated Press via NOLA.com on the 2009 “on hold” status and project details.

Rolling Stone “Trump Vowed to 'Stand Behind' New Orleans After Katrina” (Lorena O’Neil, August 2025) on Trump’s post-Katrina promise and project failure.

IBEW investigation (2016) noting Trump Tower N.O.’s deposits and foreclosure.

Houston Architecture Forum archives (quoting Times Picayune 2005) on the Florida developers (Levin, Rinke, Mowe) and Portofino tie-in.

Planetizen News (March 2005) on City Council approval and project specs.

Florida Trend “Paving Over Paradise” (March 2009) on Portofino’s environmental battles.

Tampa Bay Times (May 2005) reporting on wetlands mitigation for Portofino.

Levin Rinke Realty Press Information on Portofino Final Phase (2016).

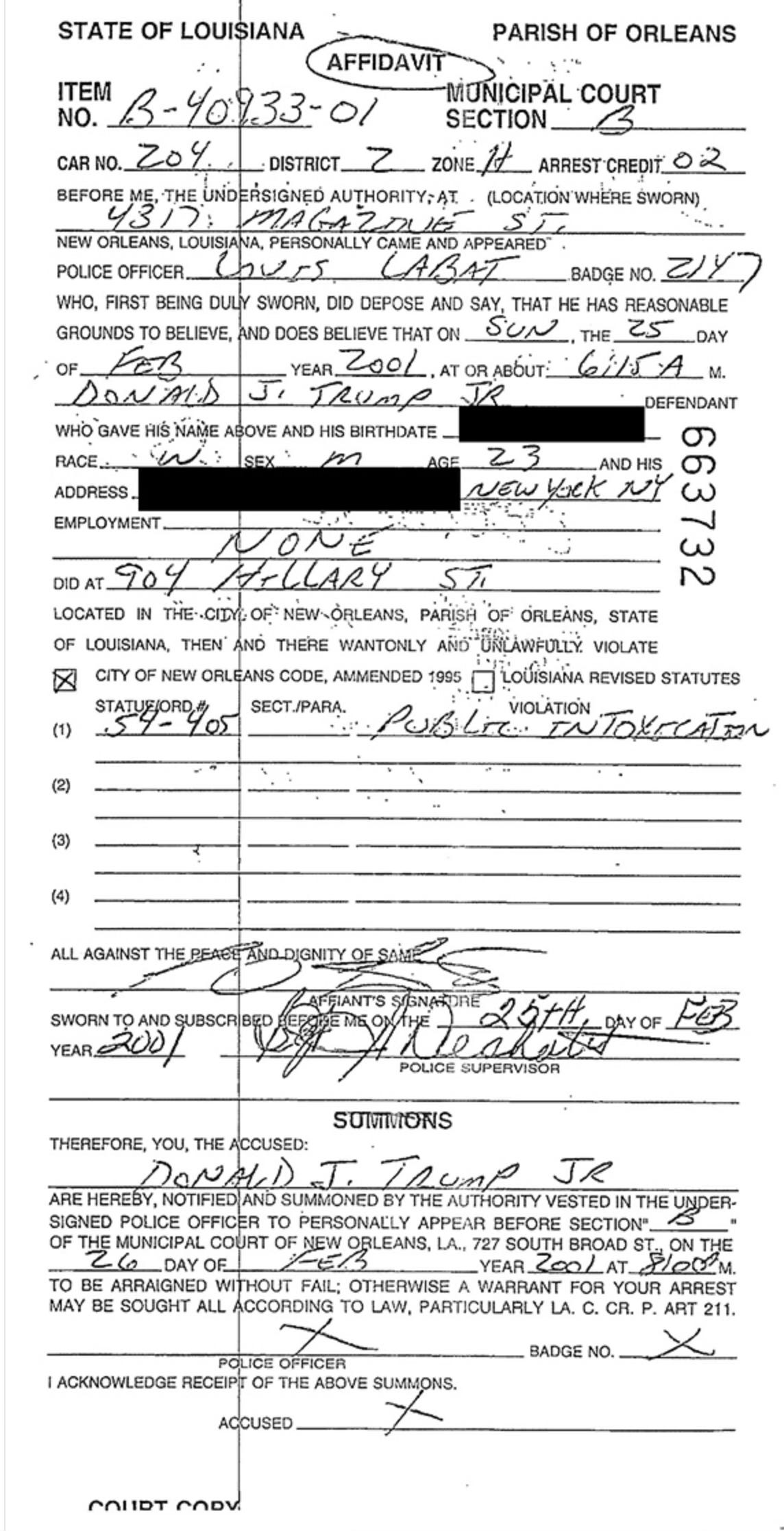

Four years earlier, at 6:15 a.m. on the Sunday before Mardi Gras, Donald Trump, Jr. was picked up by the New Orleans police outside of a home on, of all places, Hillary Street, and charged with public intoxication.

The records related to his arrest, which only became public in 2020, indicate that he spent the night behind bars before posting a $300 bond at 8:00 a.m. on Lundi Gras. Charges were eventually dropped after Trump, Jr. returned to town for a court hearing on July 25, 2001, and entered a plea of not guilty.

In a twist of history, Edwards would later be convicted for rigging the selection of casino operators and sentenced to a decade behind bars in a convoluted case considerably influenced by San Francisco 49ers owner Eddie DeBartolo’s decision to plead guilty to lying to the FBI about giving a $400,000 “bribe” to Edwards for help in acquiring a casino license. In his first term as president, Donald Trump granted DeBartolo a pardon but not Edwards.

In his three presidential elections, Trump easily carried the state of Louisiana by double digits, but in the deep blue bastion of Orleans Parish, he mustered only 15% of voters in 2016, 15% in 2020, and 15% in 2024.

Incidentally, in 2005, Donald Trump lost a $5 billion lawsuit against author Timothy O’Brien, whom Trump accused of defamation after O’Brien claimed that Trump’s net worth was between $150 and $250 million in the book TrumpNation: The Art of Being the Donald.

I never heard much of this before. The tangled webs we weave.