Tailing Ferrie's Comet

On Nov. 22, 1963, Dave Ferrie danced out of a courthouse, partied with a mob boss, & sped into the darkness to take an 18-year-old boy ice-skating in Texas, a trip that would haunt him to death.

“[New Orleans] is not a city prone to knowing what it’s doing before it arrests people.”

—Dave Ferrie

In the late evening of November 22, 1963, as Captain David W. Ferrie’s brand-new light blue 1961 Comet streaked westward through the blinding rain, escaping the vortex of New Orleans and into “the whirlpool of despair,”12 a massive flotilla of federal agents dropped anchor in the Crescent City, the first invasion of investigators dispatched to Louisiana in order to gather information about Lee Harvey Oswald, the 24-year-old ex-Marine and New Orleans native suspected of assassinating President John F. Kennedy earlier that day in Dallas. Dave Ferrie couldn’t have picked a worse possible time to skip town.

“All I wanted to do was relax,” Ferrie explained to 31-year-old Andrew “Moo Moo” Sciambra, a baby lawyer working for Orleans Parish District Attorney Jim Garrison. “As it turned out, it was the worst trip I’ve ever made in my life.”

Ferrie didn’t make the midnight drive from his apartment in New Orleans to Houston during a terrible storm so he could “relax” once he checked into Room 19 of the Alamotel on 8700 South Main Street. He wanted to continue partying. The rest of the country may have been in mourning, but the disgraced former airline pilot finally had something worth celebrating. He brought along two friends, 18-year-old Alvin Beauboeuf and 24-year-old Melvin Coffey. They were always ready for an adventure.

Mel Coffey, who worked for Boeing on building the S-1C, the first stage of NASA’s Saturn V rockets, at the Michaud Assembly Factory in New Orleans, suggested Cape Canaveral and nearby Merritt Island, Florida, home of the brand-new NASA Launch Operations Center, which, in one week, would be given a new name by President Lyndon B. Johnson: The Kennedy Space Center. But the drive was 700 miles from New Orleans, and Al Beaubouef had his heart set on something else. He wanted to go ice skating, and he’d heard there was a new rink in Houston. Beaubouef made Ferrie promise to take him, and so Houston it was.

“I was a former roller skating champion with dozens of medals. I wanted to see how good I’d do on ice,” Beauboeuf recalled to researcher Gus Russo. “I had convinced Dave that ice skating was going to be the next big thing—like disco became in the seventies.”3

Layton Martens, a regular presence and occasional roommate at Ferrie’s apartment, remembered asking why he was even considering driving all the way to Houston just so Beaubouef could go ice skating. Ferrie told him that he “might be interested in purchasing a skating rink,” Martens said.

For his part, Dave Ferrie readily acknowledged that ice skating was at the top of their agenda, but he also said they planned on goose hunting as well. Plus, he had business to do in Vinton, Louisiana, he said, and Beauboeuf had family to visit in Alexandria. However, Ferrie didn’t ice skate at Winterland, and although they saw geese, no one went hunting. They left Houston on Saturday night and headed to the beaches down in Galveston. But it was freezing and miserable, and they packed up early the next morning and made their way to Alexandria.

Stopping at a service station outside of Orange, Texas, to replace the car’s sparkplugs, Ferrie watched Jack Ruby shoot and kill Lee Harvey Oswald on live television. Asked about the specifics of their itinerary, Ferrie wasn’t sure when or why he was in Vinton, but he recalled they had intended to stay in Alexandria for two or three days. Instead, they left only an hour after arriving. Ferrie had called Martens, who was staying at his apartment, to check on things back home.

“You need to get back home,” Martens told him. “Someone from WWL just called asking about you and Oswald, and your lawyer stopped by this afternoon looking for you. He said something about Oswald having your library card with him.”

Ferrie, Beaubouef, and Coffey piled back into the Comet station wagon and bolted back to New Orleans. Ferrie had been attempting to reach his attorney and part-time employer, Wray Gill, to no avail, and along the way, he stopped several times at pay phones to try Gill before finally reaching him.

“I think they want to arrest you,” Gill warned him.

“Who?”

“Garrison.”

Ferrie was dumbfounded, terrified, and fuming with anger. “What should I do?”

“Get back home, and we can go to their office tomorrow.”

Ferrie later said that he pulled into New Orleans around 7:30 p.m., but given the timeline of events that followed his return, he likely didn’t make it to his apartment until 11:30 p.m. He wouldn’t step foot inside, however, until late the next day. He knew Layton Martens was there, but he had no idea what awaited him. He asked Al Beaubouef to be a decoy, which was fine by Beaubouef, who wanted to call a few girls and invite them over. In the meantime, Ferrie needed to drive Coffey home anyway.

On his return shortly after midnight, he spotted a group of people standing out front and several unmarked cars parked along the side of the street. He wasn’t taking any chances, and fortunately, he knew he was too far away and it was too dark outside for anyone to have noticed him. He turned the car around and headed to a nearby grocery store, where he used the payphone outside to call his home line. After a few rings, a stranger picked up—“some dumb ox,” Ferrie remembered—and he knew immediately that his apartment was being raided.

With Dave Ferrie nowhere in sight, police decided to haul Al Beaubouef and Layton Martens into the Second District Police Station and book them for vagrancy and for being “under investigation of subversive activities.”

Ferrie knew he couldn’t return home, and it was probably better if he left New Orleans for the night. The police were actively looking for him. He phoned Wray Gill and briefed him on the nighttime raid.

He steered his Comet to Baton Rouge, more than an hour away, but once there, he became paranoid about getting a hotel room for the night.

Thomas Compton, one of his former CAP cadets, he realized, was now a college student in Hammond, fifty miles east. Ferrie would claim later that he called Compton once he made it to Hammond, but according to Compton, Ferrie surprised him by showing up at his dormitory at 5:30 a.m. in hysterics. “The police are at my home and have taken some of my things,” he cried. Compton had no clue what he meant, and Ferrie never mentioned his trip to Texas. He phoned Wray Gill and left Compton’s dorm around 8:30 a.m.

That afternoon, Wray Gill accompanied his client to the Orleans Parish District Attorney’s Office, and Captain David William Ferrie, accused of flying to Dallas to smuggle a suspected murderer out of jail and into hiding, turned himself in, becoming the first person arrested for conspiring with Lee Harvey Oswald in the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

“I had no idea [the trip to Texas] would turn out to be a stupid move. It was just a spur-of-the-moment thing for relaxation.”

—Dave Ferrie

For Dave Ferrie, the joy was always in the journey, driving through an expanse of darkness for hours, flying into empty skies, ensconced in the power behind the steering wheel, a captain in control of his craft. He spent most of his life moving through liminal spaces, concrete highways and blue skies, college classrooms and cheap hotels, airport terminals and doctor’s offices. Whenever he wasn’t in transit, he found himself a stranger in a strange land, no matter where he was. Captain Ferrie was most comfortable in a uniform. He preferred wearing his rank subtly and without worrying about the frivolities of fashion. He struggled with people who failed to recognize his importance or respect his intellect.

Ferrie was high-octane, loud, and obnoxious and full of profanities, someone who brimmed with nervous energy and who had an opinion about practically everything. There was at least one thing he never claimed, at least publicly: He was gay. His sexual orientation made him automatically suspicious in the New Orleans of the 1950s and 60s, a time when the City That Care Forgot cared far too much about gay men.

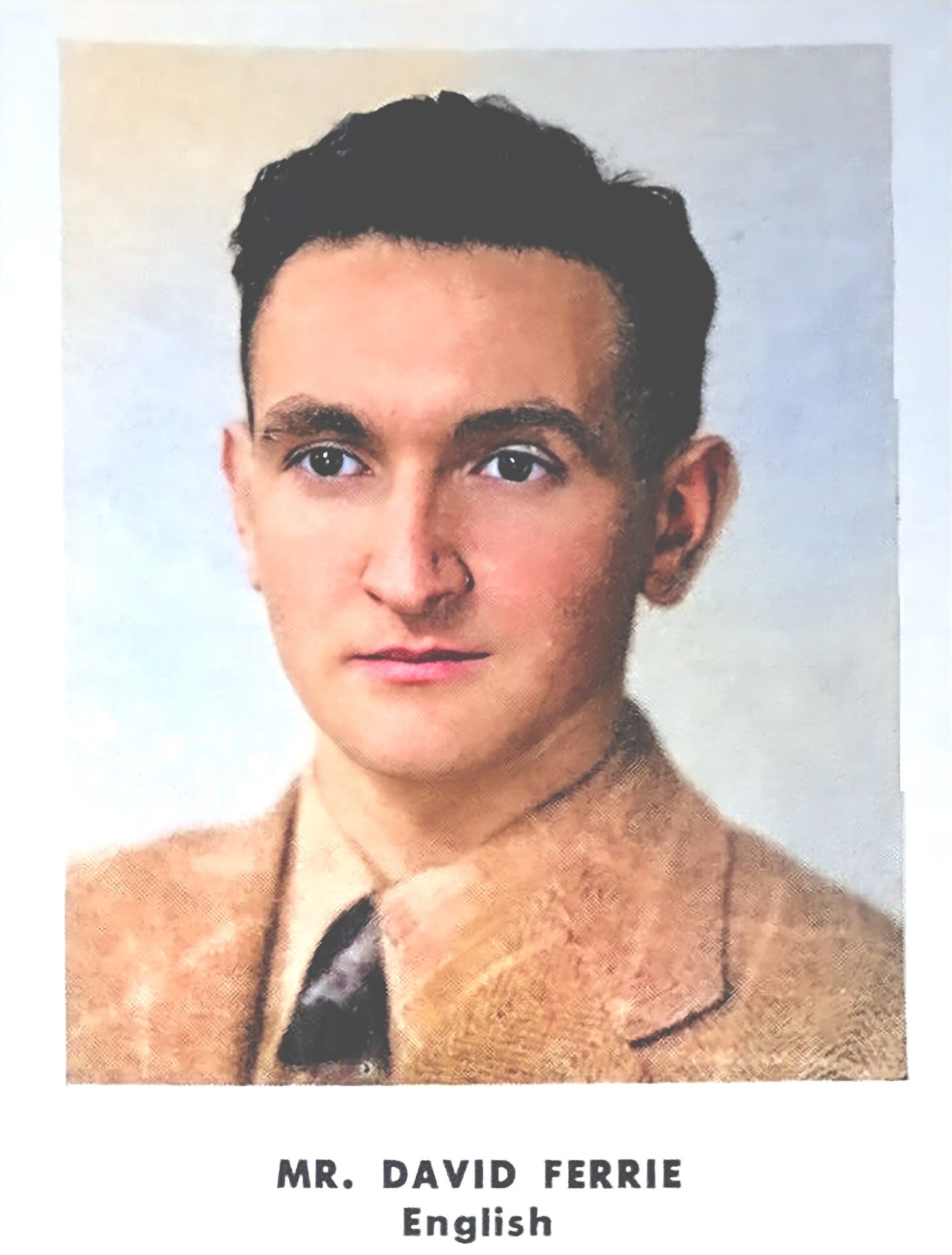

Dave Ferrie was a pilot first, and by all accounts, a damn good one. He’d also been a priest, psychologist, private eye, pianist, patriot, and polemicist. At least, he tried to be. Seminary took a toll on his mental health. He dropped out twice from two different schools.

In the New Orleans city directory, he listed himself as “Dr. David W. Ferrie, psychologist,” but his doctorate in psychology was a bogus degree from an unaccredited mail-order mill in Bari, Italy. Neighbors would tell reporters and investigators that they assumed he ran a practice out of his apartment. He was a gifted private investigator, but his notoriety made it difficult to find stable work and impossible to “blend in.”

A pianist? He hadn’t played in years. A patriot? That’s a matter of opinion. He was proud of his longtime involvement in the Civil Air Patrol, a congressionally chartered nonprofit organization that served as the civilian auxiliary of the United States Air Force, but his relationship with CAP was tumultuous and controversial. He was kicked out multiple times and even attempted to launch his own “independent,” unsanctioned squadron, which, one could argue, made him a defector.

As a polemicist, he could be persuasive, but too often, he undermined his credibility with crude language, ad hominem attacks, and appeals to his own authority. He also didn’t know how to read the room.

In July 1961, for example, he was invited by the local chapter of the Military Order of the World Wars to deliver the keynote for its regular meeting. “The speaker of the evening, Captain D. W. Ferrie, Senior Pilot, Eastern Airlines, spoke on Cuba—April 1961, Present, Future,” Frank Speiss recorded in the minutes. “At the opening of his presentation, he indicated his talk would be controversial. When partly through the presentation, the Commander rose, apologized for interrupting the speaker, and told him the tenor of his remarks, up to that point, were contrary to the preamble and objectives for which the Military Order of the World Wars stands and that if he wished he could speak, not as our guest speaker, but as a private citizen and to the members present as private citizens after adjournment of the meeting. Captain Ferrie determined he would stop his presentation.”

Ferrie was undeniably intelligent. An autodidact who owned more than 3,000 books, he taught himself to become a hypnotist, an engineer, a forensic scientist, and a medical researcher.

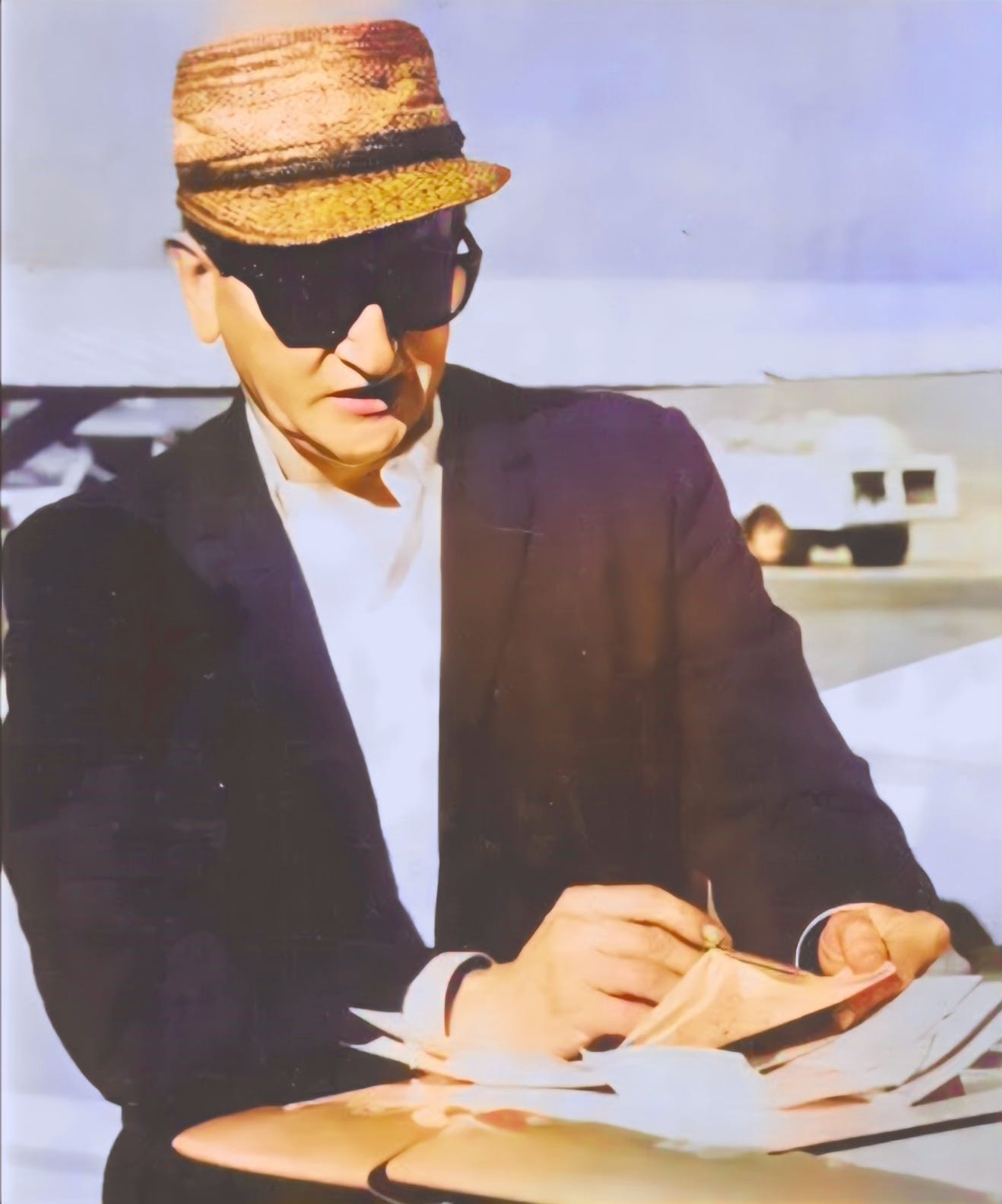

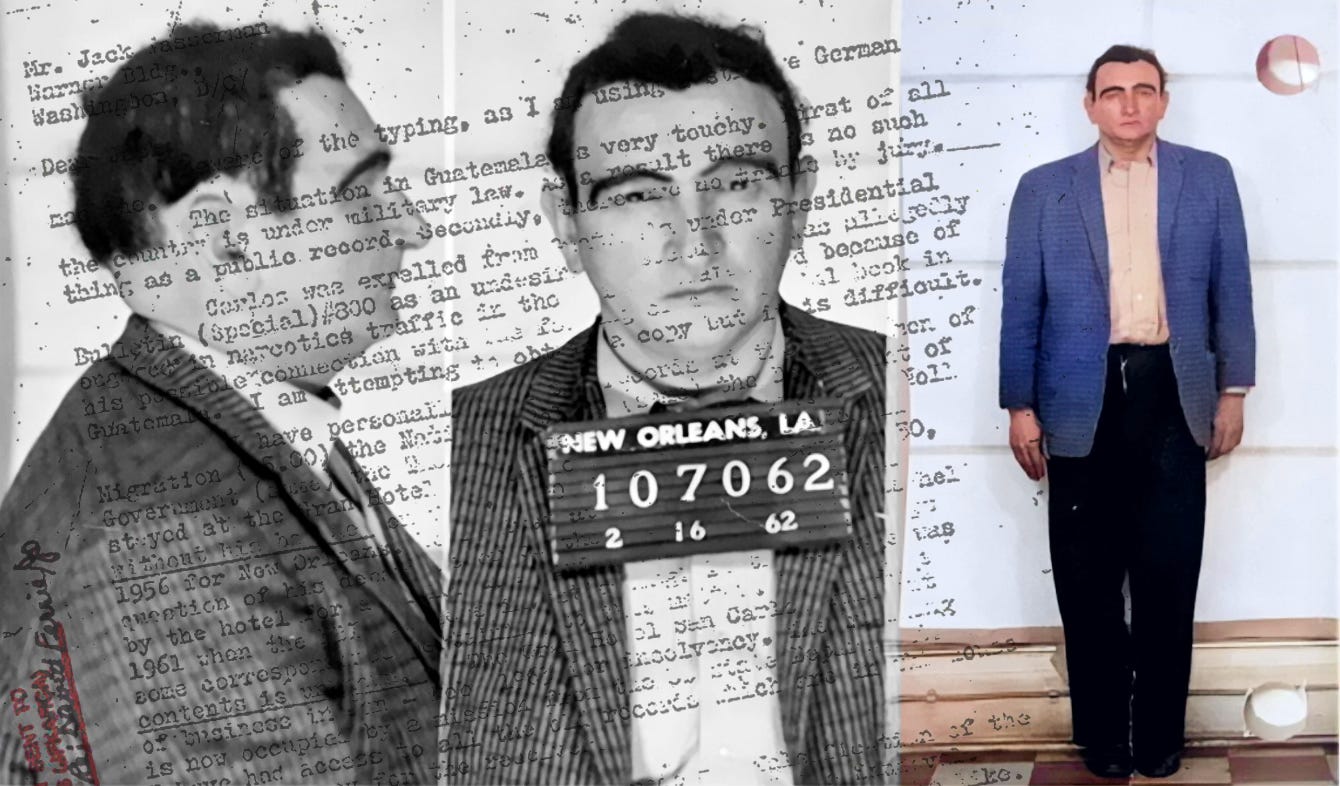

But the most memorable thing about Dave Ferrie wasn’t his job, skills, or talents. It was his appearance: Weathered but smooth skin, dark brown, owl-like eyes, thin lips that disappeared under a protruding nose. Alopecia had taken all of his hair when he was in his mid-thirties. Whenever asked about his hair loss, he would tell fantastical stories about chemical weapons, medical experiments, and battery acid. One of his former colleagues at Eastern Airlines had a different theory.

“When Ferrie first joined the line, he was ‘handsome and friendly,’” the person, who asked to remain anonymous, told Ramparts magazine, “but in the end became ‘moody and paranoiac.’ The personality change coincided with a gradual loss of hair.”

But his alopecia was permanent, suggesting the causes were likely either genetic or the result of an autoimmune disorder. It couldn’t have been stress-induced. He typically wore a hat and sunglasses when he went out, which were effective at concealing his condition. For a man whose grooming habits and hygiene had always been wanting, Ferrie struggled with toupees. He usually wore a dark red wig that he never bothered to comb or wash. The only thing he knew to do with his eyebrows was to paint them on with thick layers of mascara.

The press was ruthless about his condition. “Besides the facts surrounding his life, Ferrie himself was a singularly repelling figure physically,” Haynes Johnson of the Washington Star wrote. “He was sickly, and his hair and eyebrows had been burned off. Instead of buying an adequate wig, Ferrie affected a different, more striking device. He glued down his red toupee and false eyebrows with glucose cement.”

"I know where you were the day Kennedy was assassinated. You were cooling your heels with me in Federal District Court.”

—FBI New Orleans Bureau SAC Regis Kennedy to David Ferrie

In the days and years that followed the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, David Ferrie, whom Garrison called “one of history's most important individuals,” would emerge at the nexus of an entire universe of conspiracy theories surrounding the assassination of the 35th President of the United States: Cuba, the CIA, the Mafia, and most notoriously, Garrison’s theory of a “homosexual thrill-killing.”

Dave Ferrie started to regret his decision to leave New Orleans before he even arrived in Houston. He wasn’t paranoid. If anything, he was worried that the investigation wouldn’t include him. He spent most of his time at the Alamotel and the Winterland Ice Skating Rink on the phone, mining his sources back home for information about Oswald.

Unbeknownst to Ferrie, shortly before midnight on Saturday, November 23, his former colleague turned arch nemesis, Jack S. Martin (aka Edward Stuart Suggs), a slender man who sported a pencil-thin moustache, was also busy making calls. Hearing reports that Oswald, as a teenager, had once been enrolled in a local Civil Air Patrol squadron, Martin, a notorious drunk, began spreading a series of increasingly alarming rumors about his old pal, Dave Ferrie, whom he knew was a former CAP commander. Ferrie, he claimed, was friends with Oswald, and, recalling the weapons he’d seen at Ferrie’s apartment, Martin asserted that Ferrie had taught the suspected assassin how to use a rifle equipped with a telescopic sight, the kind Oswald used from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository Building.

When one of Ferrie’s friends, Hardy Davis, a Black, gay bail bondsman, mentioned that Ferrie skipped town for Texas for the weekend, Martin cooked up a story about Ferrie flying to Dallas with plans of extracting Oswald from the scene of the crime. He added a minor embellishment that would become a significant detail for conspiracists: Oswald, he said, had Dave Ferrie’s New Orleans library card in his wallet when he was arrested.

Martin’s story was entirely fabricated: Ferrie and Oswald weren’t friends. Ferrie owned firearms, including a rifle, but he was never especially interested in guns or marksmanship and had no idea how to use a telescopic sight. He didn’t fly to Dallas; he drove to Houston. And Oswald, who lived in his hometown of New Orleans for five months in 1963, had his own well-worn New Orleans library card, which was issued to him on May 21 by an assistant librarian at the Napoleon Avenue branch, about a half a mile from his house on 4907 Magazine Street, in the wallet he’d left at Ruth Paine’s home in Irving, where his wife Marina and two daughters, June and Audrey, lived full-time and where Oswald spent most weekends.

In an internal FBI memorandum dated November 25, 1963, New Orleans Bureau Special Agent in Charge Regis S. Kennedy pulls no punches: “Jack Martin is a well-known self-styled New Orleans private eye, personally known to SA Kennedy as a psychopathic personality, an individual who is not above furnishing false information. He is a ‘hang out’ at the New Orleans District Attorney's Office and closely with Guy Banister, a former Bureau SAC who is now operating a private investigation agency in New Orleans. Martin has an extremely poor reputation for the truth and veracity and [is] regarded by most people who know him as a ‘nut.’”

Martin was drunk and delusional, but as a professional con artist, he was an expert at spreading vicious rumors and launching smear campaigns. He knew who to call, when to call them, and what to say to attract attention, appear credible, and maintain plausible deniability. He called his contacts in the New Orleans Police Department and then the television stations WWL and WDSU. Eventually, he reached out to Orleans Parish assistant DA Herman Kohlman at home, repeated the stunning allegations against Ferrie, and implied that he’d heard the rumors from the press. Kohlman phoned a contact at WDSU to ask what he’d been hearing about Ferrie. Neither man revealed their sources. If they had, they would have realized Jack Martin was playing them. Before calling it a night, Kohlman reached out to another assistant District Attorney, Frank Klein, to brief him about the tips he’d received. Frank Klein decided to call an emergency meeting.

“At about midnight on [Sunday] November 24, 1963, Officers R. Comstock, L. Ivon, C. Jonau, C. Neidermier and F. Williams met Assistant District Attorney Frank Klein, in the office of the District Attorney,” Sgt. Fenner Sedgebeer memorialized in a letter to New Orleans Superintendent of Police Joe Giarrusso a few months later. “At that time, Mr. Klein began an investigation as to the possibility of David Ferrie being involved in the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, which had occurred in Dallas on November 22, 1963 by the hands of Lee Harvey Oswald. Information had been brought to the attention of Mr. Klein that David Ferrie and Lee Harvey Oswald had been friends and associates in the past.” The NOPD and the DA were planning a late-night raid of Ferrie’s apartment, intending to take him into custody. Since they were operating under the assumption that Ferrie had conspired with Oswald, they considered him a “fugitive from the State of Texas,” even though Texas had not declared him one.

Like the rest of the world, Dave Ferrie learned of Oswald shortly after his apprehension in Dallas on November 22. He didn’t recognize the name, Lee Harvey Oswald, and had no memory whatsoever of an Oswald in the Civil Air Patrol. Like the rest of the world, Dave Ferrie was curious to know more about the alleged assassin, particularly about his ties to New Orleans.

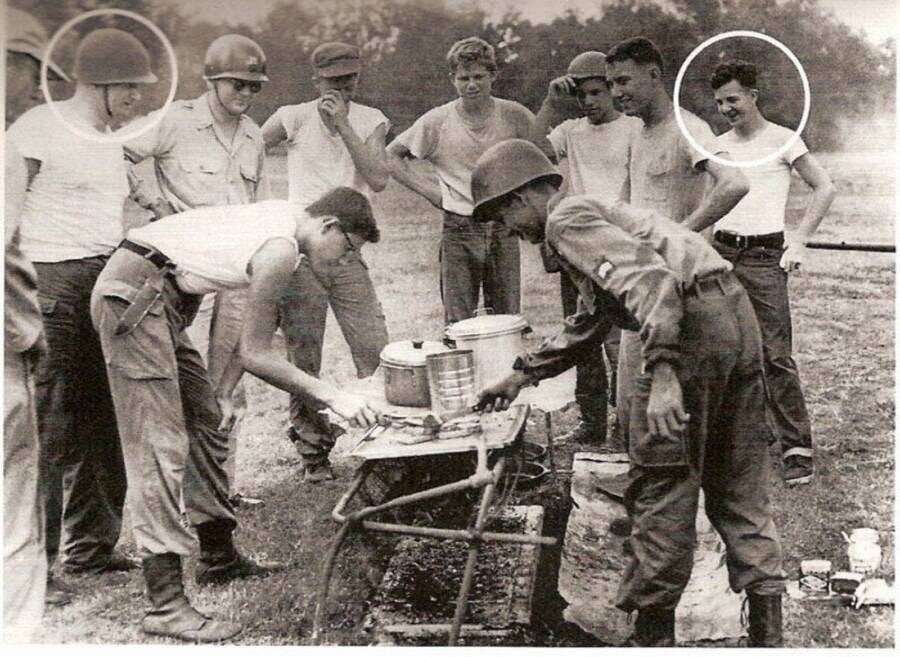

At the time, New Orleans, it’s important to note, had two CAP squadrons, one that met at Lakefront Airport in Orleans Parish, and another that met at Moisant Airport in Jefferson Parish (now known as Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport). From 1952 until April 1955, Ferrie was an instructor and eventually the commander of the squadron at Lakefront, which was larger and more prominent than the upstart Moisant. In December 1954, Squad Commander Ferrie had submitted the requisite paperwork for reappointment, but the following April, Wing Commander Joe Ehrlicher rejected his application, presumably in response to the death of a teenage pilot who crashed during flight training, effectively firing him from Lakefront. Ferrie was not deterred. From June through August 1955, he served, unofficially, as an instructor with the Moisant squadron.

Ferrie called several of his former CAP cadets to ask if they recalled Oswald. Everyone said the same thing he said: Never knew him, don’t remember him, didn’t even recognize his name. Everyone, that is, except for a local florist and former cadet named Eddie Voebel. Eddie Voebel remembered Lee Oswald well, he told Ferrie. They were friends in the eighth grade at Beauregard Junior High School. Voebel, in fact, was Oswald’s only friend.

By the time Ferrie phoned, Voebel had already spoken with the FBI twice. Bill Slatter of WDSU had also called Voebel to “advise” him that Dave Ferrie was “a homosexual.” Voebel hadn’t seen or spoken with the erstwhile CAP instructor in years, but now that he thought about it, he told Special Agents Nathan O. Brown and Kevin Harrigan, “Ferrie seemed to be an ‘oddball’ who rode a motorcycle and appeared very emotional.” He recalled how, on one occasion, Ferrie began to cry while listening to music. Ferrie had left a lasting impression on Voebel, but the claim that Ferrie was the “commander” of his CAP squadron didn’t ring true; he seemed to recall a different commander. Regardless, he did not doubt that Oswald and Ferrie had met one another, however briefly.

During the summer of 1955, Voebel had convinced a 15-year-old Lee Harvey Oswald to enroll as a cadet in the Moisant Squadron of the Civil Air Patrol. They rode the bus together out to Jefferson Parish for one of the meetings. Oswald, he said, attended two or three drills, four at the most. “It’s funny,” Voebel said. “I remember Oswald joining, but I don’t remember him as ever being there. He had a knack for being there and not being noticed.” Oswald, he said, claimed he was going to transfer into the Lakefront CAP squadron because the commute out to Moisant Airport took too long. Voebel was reasonably sure that Oswald never actually joined the other squadron, but he thought it was entirely possible that Oswald may have gone with him to a party for CAP recruits at Ferrie’s house.

Ferrie knew what he had to do, and he knew it would be enormously risky: He called Regis Kennedy at the FBI New Orleans Bureau and said he needed to amend his previous answer. He may not have remembered Oswald, but he trusted Voebel at his word. He also needed to amend his answer about whether he had ever met Oswald.

This excerpt is based on an exhaustive review of the thousands of pages of files in the evidentiary and investigative record, much of which was declassified and released to the public by the National Archives during the past seven years under the JFK Assassination Records Act of 1992; contemporanous news coverage, particularly the reporting of local journalists at the New Orleans States-Item and the Times-Picayune; the work of David Reitzes, the publisher of JFK-Online.com, and the late investigative researcher Stephen Roy (also known as David Blackburst), and the private notes and personal journal of Life magazine editor Dick Billings during the investigation and trial of Clay Shaw.

Immortalized by the actor Joe Pesci in Oliver Stone’s 1991 blockbuster JFK, Dave Ferrie was the subject of two recent books: A Ferrie Tale by David Beddow, a work of historical fiction published in 2019 which was primarily informed by the other book, 2014’s David Ferrie: Mafia Plot, Participant in Anti-Castro Bioweapon Plot, Friend of Lee Harvey Oswald and Key to the JFK Assassination by Judyth Vary Baker, a widely discredited conspiracist who dubiously claimed to have once dated Lee Harvey Oswald and to have known Ferrie personally. Both Beddow and Baker manipulated and distorted the record in an attempt to thread together a string of absurd but tantalizing conspiracies, and, as a result, both of their stories spun wildly before collapsing under the weight of their deceit. Baker, who spends her time today peddling an increasingly unhinged and frequently racist assortment of fringe conspiracy theories on Elon Musk’s X, is particularly insidious.

There are several other books, however, that provided valuable, credible, and unique insight into the complicated and elusive life of David Ferrie, including, among others, Patricia Lambert’s False Witness: The Real Story of Jim Garrison’s Investigation and Oliver Stone’s Film JFK (1998), Donald H. Carpenter’s Man of a Million Fragments: The True Story of Clay Shaw (2014), Fred Litwin’s On the Trail of Delusion (2020), and Alecia P. Long’s Cruising for Conspirators: How a New Orleans DA Prosecuted the Kennedy Assassination as a Sex Crime (2021).

Today, with America awash in the propagandistic conspiracy theories and “alternative facts” promulgated by a president with little regard for the rule of law or the free press, the public’s interest in pursuing the truth is routinely undermined in service to preserving the political interests of the powerful. Conspiracies are contrived to deflect and discredit, “weapons of mass distraction.” They aren’t discoveries that illuminate.

“The only excursion of my life outside of New Orleans took me through the vortex to the whirlpool of despair: Baton Rouge. In some future installment, a flashback, I shall perhaps recount that pilgrimage through the swamps, a journey into the desert from which I returned broken physically, mentally, and spiritually. New Orleans is, on the other hand, a comfortable metropolis which has a certain apathy and stagnation which I find inoffensive.” — Ignatius J. Reilly in John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces, pg. 181.

In 2013, when the Times-Picayune began putting together a package of stories commemorating the 50th anniversary of President Kennedy’s assassination, the writer Adriane Quinlan, then a recently-hired reporter and newly-arrived New Orleanian, received the heavy labor assignment: A story about the city’s conspiracists and its alleged conspirators. Nearly everyone involved had died decades ago, but Quinlan found 68-year-old Alvin Roland Beaubouef, Sr., alive and well, in St. Bernard Parish.

What did he think “put him in the middle of history?” she asked. “It was the skating they wanted me for,” Beaubouef replied.

In "The Man Who Knew Too Much", Dick Russell writes: "In Chapter Twelve we saw that Ferrie probably first encountered Oswald in 1955, when Ferrie commanded the Louisiana Civil Air Patrol in which the teenager took part. In the summer of 1963, according to Delphine Roberts, on at least one occasion Oswald and Ferrie went together to a Cuban exile training camp near New Orleans to take rifle practice. Further, many other witnesses would come forward during Frontline’s 1993 investigation, also claiming to have seen Oswald and Ferrie together at a Cuban exile paramilitary base that summer."

The HSCA uncovered film footage of the Lacombe training camp in September 1963 that shows both Oswald and Ferrie. The 8 mm reel was soon stolen.

There's also the Cadillac trip to Clinton, Lousiana that needs mention. "[A]s registrar Henry Palmer later told author Anthony Summers, “I asked him for his identification, and he pulled out a U.S. Navy ID card. I looked at the name on it, and it was Lee H. Oswald with a New Orleans address.” Oswald told the registrar he figured he had a better chance of getting a job at the nearby East Louisiana State Hospital if he registered as a voter in Clinton. Palmer found the request strange, finally told Oswald that his time in the area was too short to qualify for registration, and Oswald thanked him and left. Six witnesses told the House Assassinations Committee of seeing Oswald in Clinton that day. Several of these also got a good look at his two companions waiting in the Cadillac. The driver was a big, gray-haired man with a ruddy complexion. Garrison became convinced it was Clay Shaw, the key figure in the DA’s conspiracy case. Shaw’s identification by crucial Clinton witnesses confirms this. And the other passenger was positively identified by CORE [Congress of Racial Equality] chairman Corrie Collins as David Ferrie. “The most outstanding thing about him was his eyebrows and hair,” he said. “They didn’t seem real.” The reasons behind Shaw’s presence in Clinton remain a mystery, but Ferrie was well known as an outspoken opponent of actions like the CORE campaign."